SPLC on Campus: A guide to bystander intervention

What’s worse than being targeted for harassment because of who you are? Enduring the harassment while surrounded by bystanders who see what is happening, but do nothing.

Public harassment and hate violence frequently make headlines in the United States. While news reports sometimes feature inspiring accounts of bystanders intervening to stop such attacks, many incidents don’t end as uplifting tales about good Samaritans. They are stories of bystanders frozen in the moment. Other times, people intervene only to find themselves targeted.

It’s understandable that people can feel immobilized and afraid when faced with these situations. There’s no need, however, to feel helpless. We can all find a way to safely take action that makes a difference. This guide provides those steps. It also examines how to prepare before you encounter such situations. As this guide makes clear, a little preparation can help you find a way to let someone know they are not alone and public harassment will not be tolerated.

Harassment and hate violence have far-reaching effects for the person targeted as well as the community. The individual may experience psychological effects after the incident, such as depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder.

It can also affect the person’s behavior in other ways. They may change jobs or skip school to avoid harassment. Some people may go as far as moving to a new community. As for the community where the incident occurred, the overall quality of life can suffer because bigotry went unanswered. Inaction can be seen as acceptance, which can allow hate to persist and grow, potentially leading to more incidents.

Public harassment or hate violence can occur unexpectedly in virtually any location. It may be on a bus, at school, at a shopping center, in a park or at any number of other public spaces. The unpredictable nature of such harassment can leave us feeling unprepared when an incident occurs. If you remember four key points, however, you can effectively respond.

1. Know what public harassment looks like. Understanding that harassment is happening – and why it’s happening – is the first step toward effective intervention. Recognize that harassment exists on a spectrum of actions ranging from hurtful comments and gestures to violence. The type of bigotry fueling the harassment can also run the gamut. Racism, sexism, ageism, classism, xenophobia, homophobia or religious discrimination are a few examples.

2. Be aware of your identity before taking action. Look at who you are – or who you are perceived to be – at the intersection of race, sex, religion, color, gender, size, orientation, ability, age and origin. Aware- ness is important because a harasser may target you for your identity. In other words, your direct intervention could escalate the situation.

If you share the same identity as the person committing the harassment, if you wield some authority, or if you are otherwise part of the dominant culture, your identity may allow you to de-escalate the situation by speaking to the harasser or intervening in a manner in which others are unable.

Whatever your identity, it’s important to tap into your experiences to effectively respond. Remember a time when you may have been targeted for harassment or hate violence. It may have been last week or when you were younger and bullied in school. By reflecting on your own experiences, you will be able to empathize with the person targeted, which is important for effective intervention.

Just as you may not have been able to respond when you were targeted, it’s important to remember that the person targeted may feel the same way. And if nobody came to your aid, you should remember what you would have wanted a bystander to do.

If you have never been harassed, imagine what it might feel like to be targeted. What would you want someone to do? If you know someone who has been harassed, tap into their experiences when you encounter an incident. These measures can help prepare you to act when you might otherwise find yourself on the sidelines.

3. Recognize your blocks, or reasons why you may not intervene. We all have such blocks. Sometimes we’re scared. Other times, we may feel we can’t make a difference – even if we act. We may believe it’s simply not our problem, especially if no one else is doing anything. We might minimize the harassment or not even recognize the behavior as harassment. (A list examining some of the most common blocks – and why we should still take action – are examined elsewhere in this guide.)

Whatever reasons stand in your way, the most important thing is to be aware of your blocks before choosing one of “The Five Ds of Bystander Intervention” that works for you.

4. When an incident occurs, choose one of "the five Ds of bystander intervention.” Each of the Ds offers a clear path of action. They include the following: Direct (directly addressing the incident); Distract (using distraction to stop the incident); Delegate (asking for help from a third party); Delay (taking action after the fact); and Document (recording the incident). We examine how you can use the Ds in the next section.

DIRECT

Direct intervention has many risks, including the harasser targeting you. Exercise it with caution. You may, however, want to directly respond to an incident by confronting the harasser, or stating to everyone that what’s happening is inappropriate or disrespectful.

Before you respond, assess the situation: Are you safe from harm? Is the person being harassed safe from harm? Does it seem unlikely that the situation will escalate? Can you tell if the person being harassed wants someone to speak up? If you can answer “yes” to all of these questions, you might choose a direct response.

Some of the things you can say to the harasser include, “Leave them alone,” “That’s inappropriate,” “That’s disrespectful” or “That’s not OK.” The most important thing is to keep it succinct. Do not argue or debate the harasser, since this is how situations escalate. If the harasser responds, assist the person targeted instead of engaging.

DISTRACT

Distraction is a subtler and more creative way to intervene. The goal is to interrupt the incident by engaging with the person targeted. Ignore the harasser. In fact, don’t talk about or refer to the harassment. Instead, talk about something completely unrelated. You can try the following:

-

Ask for the time.

-

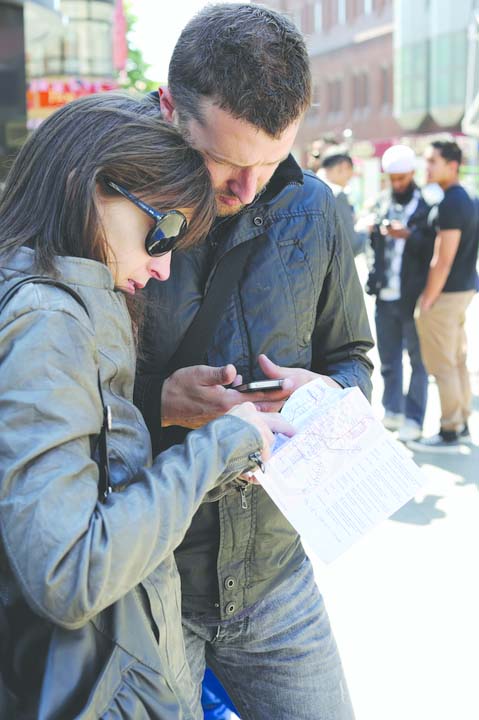

Pretend to be lost. Ask for directions.

-

Pretend they are your neighbor, colleague or friend.

-

Strike up a conversation about something random. It can be something as simple as complimenting the person’s shoes.

Of course, read the situation and choose your approach accordingly. The person targeted will likely catch on, potentially de-escalating the situation.

DELEGATE

When you delegate, you turn to a third party for help. There are a number of ways to take this approach. Here are a few examples:

-

If you are in a store, contact the manager.

-

If you are on a bus, speak to the driver. You can take a similar approach on a train by speaking to the conductor, ticket inspector or other employee.

-

If you are near a school, contact a teacher or someone at the front desk. You can do the same if the incident is occurring on a college campus. You can also contact campus security.

-

Use teamwork to distract and delegate. You can have a friend use one of the distraction techniques to interrupt the harassment long enough for you to find someone to help. If you are not with a friend, speak to someone near you who notices what’s happening and might be in a better position to intervene.

DELAY

Many types of harassment happen before anyone can intervene. If you can’t take action in the moment, you can make a difference afterward by checking on the people targeted. Here are some ways:

-

Ask if they are OK. Tell them you’re sorry about what happened.

-

Ask how you can help.

-

Offer to accompany them to their destination. You can also offer to sit with them for a moment.

-

Share resources, such as contact information for advocacy groups that can help. If they want to report the incident, offer to assist.

-

If you’ve documented the incident on video – or in any other medium – ask them if they want it.

DOCUMENT

It can be really helpful to record an incident as it happens, but there are a number of things to keep in mind to safely and responsibly document harassment.

• Assess the situation. Is anyone helping the person being harassed? If not, use one of the other Ds.

• If someone else is already helping the person, assess your own safety. If you are safe, start recording. Keep the following tips in mind:

-

Keep a safe distance from the incident.

-

Make your video easy to verify by filming landmarks, such as a street sign, a subway car number or a train platform sign.

-

Clearly state the date and time.

• Always ask the person harassed what he or she wants to do with the recording. Never livestream the video, post it online or otherwise use it without the person’s permission. Harassment is a traumatic and disempowering experience. Using a video without consent can make the person targeted feel more powerless. If it goes viral, it can raise the individual’s profile when they do not want attention, potentially leading to more victimization. Quite simply, publicizing another per- son’s traumatic experience without consent is not helpful.

Remember, everyone can do something. One of the most important things we can do is to let the person who is targeted know – even if it is through a small gesture – that they are not alone. Research shows that an action as simple as a knowing glance can significantly reduce trauma for the person harassed.

There’s no shortage of reasons – or personal blocks – that may keep us from intervening when we witness harassment. Here are a few of the most common blocks and why we shouldn’t let them stop us from responding.

“I’M SCARED.” One of the biggest reasons for not intervening is fear that the harasser will target us. It is natural to be concerned for our own safety. And it is important to think about it. It should be clear from “The Five Ds” that there are a variety of ways to safely intervene without confronting the harasser. Choose one of the Ds that is the safest approach for you.

“IT’S NOT MY PROBLEM.” Street harassment and hate violence are everyone’s problem. They impact the quality of life for people who are targeted as well as for the people who witness them. They also shape the culture within communities, neighborhoods, campuses and workplaces. Even if you’ve never been targeted, chances are someone you care about has been harassed. Tap into their experiences when you witness harassment.

“SOMEBODY ELSE WILL DO SOMETHING.” When many people are around when harassment occurs, they may wait for someone else to say or do something. Ultimately, everyone waits and nobody acts. This is called “the bystander effect”: The more people there are in an area, the less likely they are to act. But it’s also important to recognize that when one person says or does something, others are more likely to act.

“I CAN’T MAKE A DIFFERENCE.” As this guide demonstrates, even a small gesture can be helpful. You should never forget that there are many ways to make a difference. Too often, people imagine bystander intervention as a direct confrontation with the harasser.

“IT’S HARMLESS, RIGHT?” Harassment and violence can take many forms. While some forms are blatantly harmful, verbal and nonverbal acts are sometimes brushed off as benign or “not a big deal.” The thing is, words hurt, intimidating looks make people feel unwelcome, and all of these acts have the potential to escalate into something worse.

“BUT IT’S A CULTURAL THING.” Some forms of harassment, such as catcalls and other sexual harassment in public spaces, have been nor- malized for so long that people may view it as part of the culture. It’s important to question and challenge these norms because the normalization of such harassment doesn’t lessen it's harm.

Ten Ways to Fight Hate: A Community Response Guide by the Southern Poverty Law Center

Speak Up! Responding to Everyday Bigotry by the Southern Poverty Law Center

Filming Hate, a guide by WITNESS

Hollaback!, an organization dedicated to ending harassment and build- ing safe and inclusive public spaces, provided its expertise and insight for this SPLC on Campus guide. The Southern Poverty Law Center is especially grateful to Emily May, Hollaback! co-founder and executive director, for encouraging this partnership, and to its deputy director, Debjani Roy, who authored the initial draft of this guide.

EDITOR: Jamie Kizzire

DESIGNER: Cierra Brinson