Prison By Any Other Name: A Report on South Florida Detention Facilities

Download the PDF - English

Descargar el PDF - Español

The detention of immigrants has skyrocketed in the United States.

On a given day in August 2019, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) held over 55,000 people in detention – a massive increase from five years ago when ICE held fewer than 30,000 people. Unsurprisingly, the United States has the largest immigration incarceration system in the world. What’s more, the federal government spends more on immigration enforcement than for all principal federal law enforcement agencies combined, according to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General.

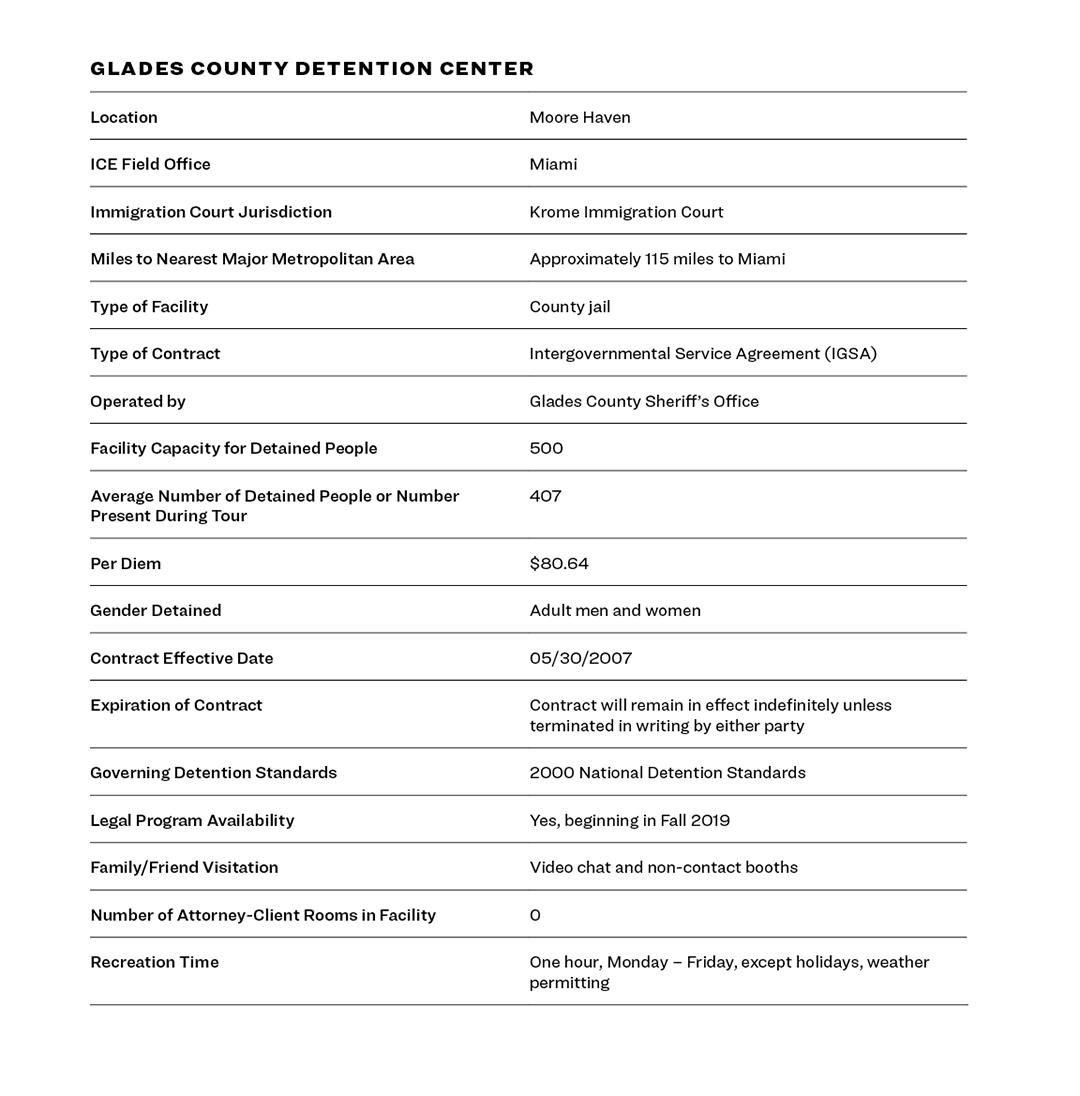

As of April 2019, Florida had the sixth-largest population of people detained by ICE in the United States, according to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University. On a daily basis, ICE currently detains more than 2,000 noncitizens in the state, mostly in South Florida, which is home to four immigration prisons: Krome Service Processing Center (Krome), owned by ICE; Broward Transitional Center (Broward), operated by GEO Group, a Boca Raton-based for-profit prison corporation; and two county jails, Glades County Detention Center (Glades) and Monroe County Detention Center (Monroe).

Despite the fact that immigrants are detained on civil violations, their detention is indistinguishable from the conditions found in jails or prisons where people are serving criminal sentences. The nation’s immigration detention centers are little more than immigrant prisons, where detained people endure harsh – even dangerous – conditions. And reports of recent deaths have only heightened concerns.

In 2018, for example, two deaths were reported by ICE at South Florida detention facilities. Luis Marcano, a 59-year-old man, died despite complaining of abdominal pain after a little over a month at Krome. Wilfredo Padron, a 58-year-old man with hypertension and pancreatitis, died after 2 ½ months at Monroe.

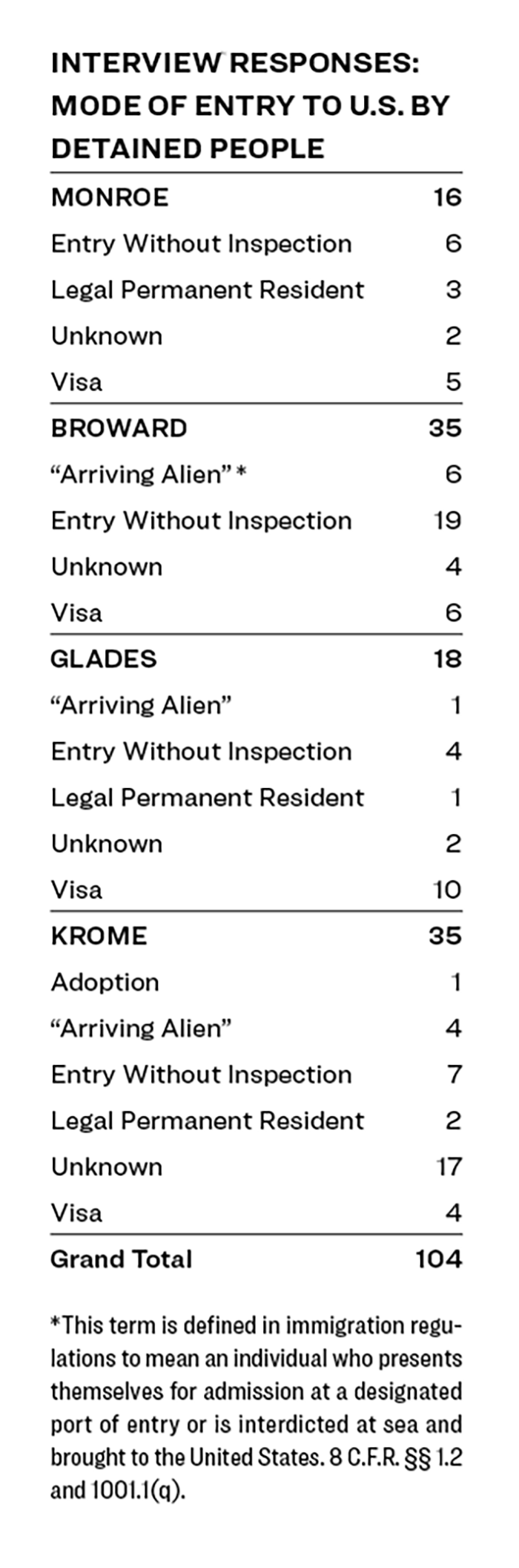

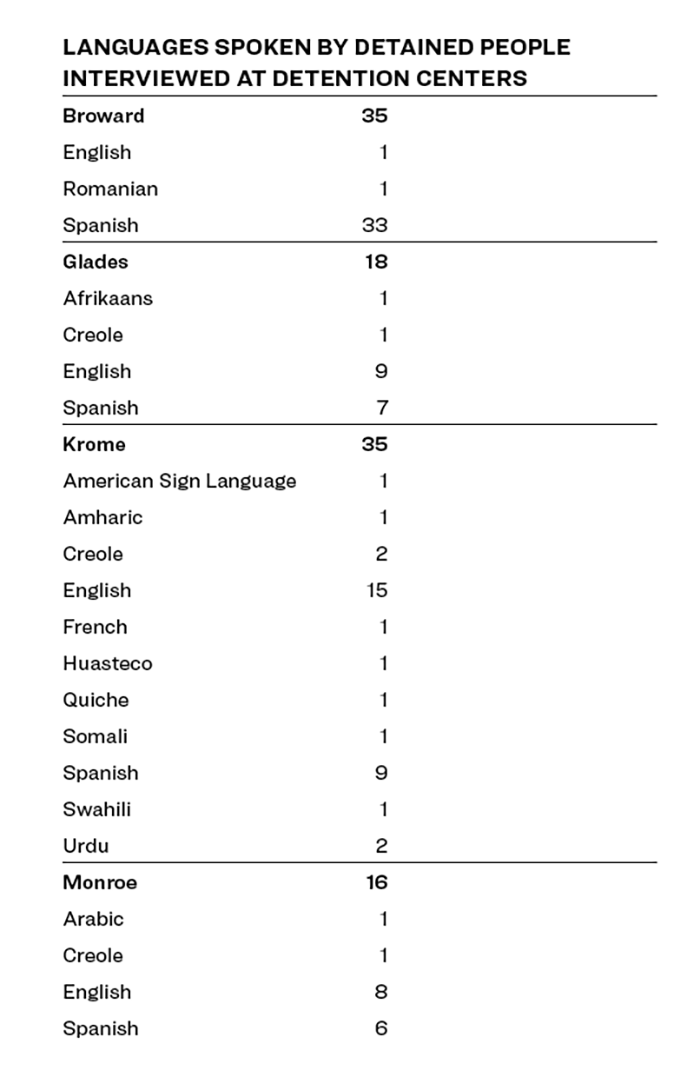

In an effort to better understand the experiences of detained individuals in South Florida, the Southern Poverty Law Center and Americans for Immigrant Justice examined immigrant detention at these four facilities. The organizations toured the immigrant prisons, requested public records, and interviewed at least 5 percent of the people held at each facility.

Our investigation found that the problems in South Florida facilities reflect what is happening in immigrant detention nationally – substandard conditions, such as inadequate medical and mental health care, lack of accommodations for and discrimination against individuals with disabilities, and overuse of solitary confinement.

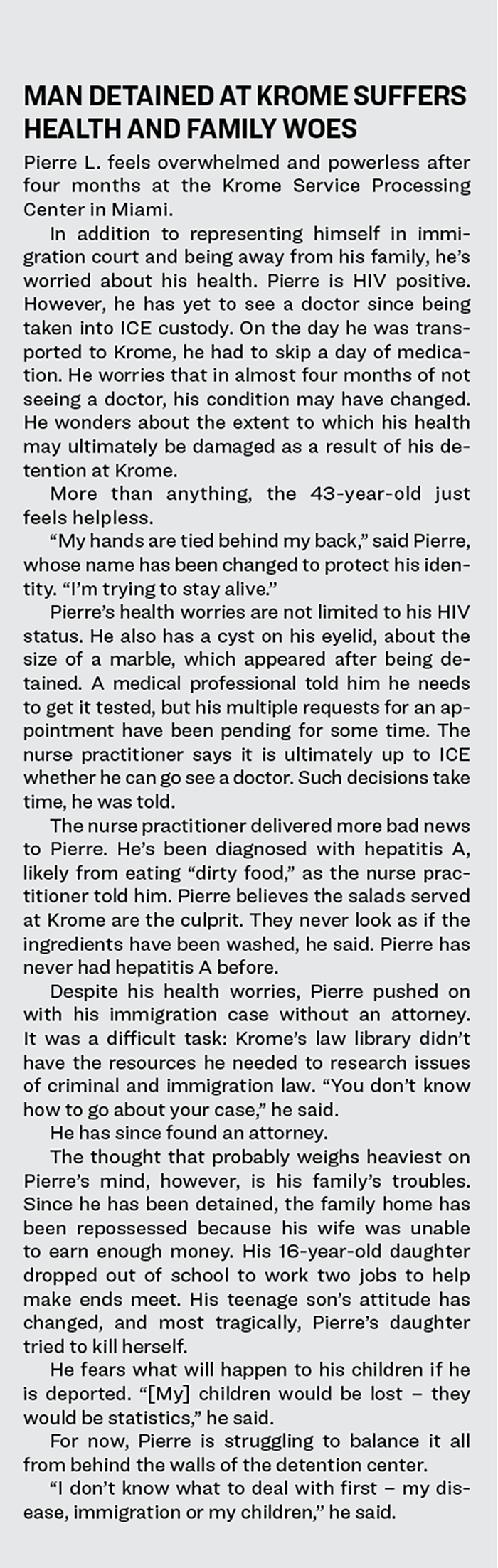

At Krome, a detained person with HIV said he had yet to see a doctor after four months at the facility. The same person was later diagnosed with hepatitis A, which he believes he contracted from eating unwashed food served at the facility. “I’m just trying to stay alive,” he said of his situation.

At Monroe, a detained person described checking a friend’s cell, only to discover he was dead. The death occurred after his friend, who used a wheelchair and had a history of strokes, was denied a request to go to the sick bay. The detained person who made the grim discovery also recounted how most of his days at the facility are spent locked inside a two-man cell.

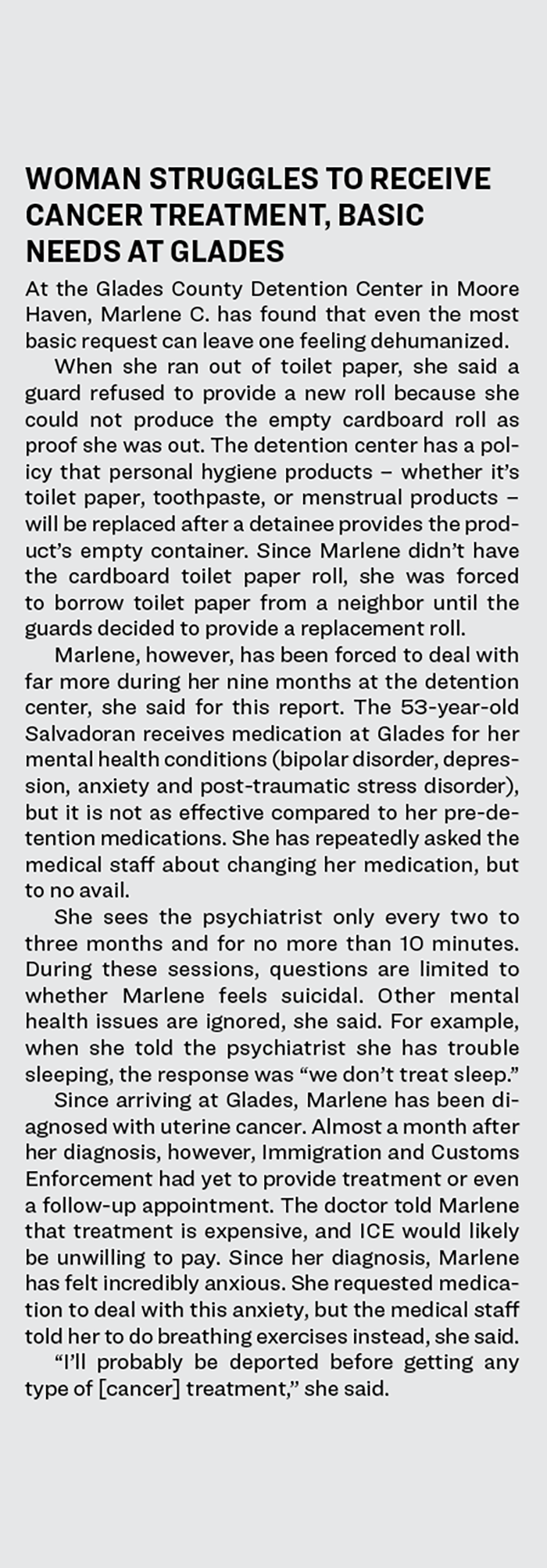

At Glades, a detained woman reported being diagnosed with uterine cancer but said ICE failed to schedule a follow-up appointment for almost a month. The doctor even told her that it was unlikely ICE would pay for her treatment. “I’ll probably be deported before getting any type of [cancer] treatment,” she said.

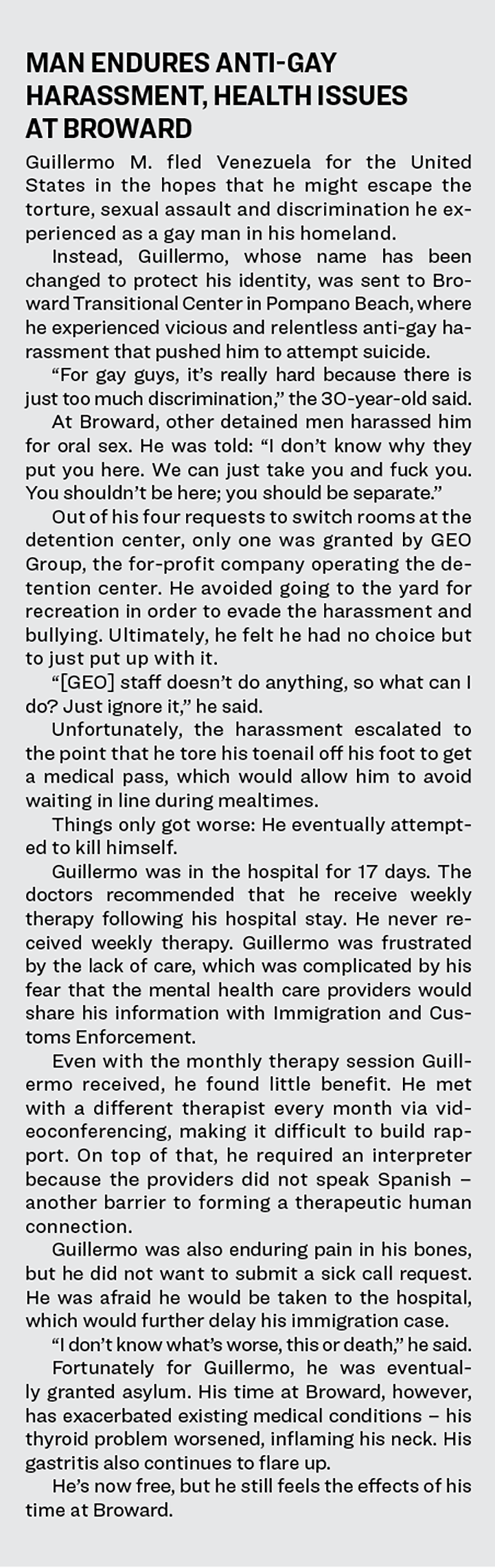

A gay man detained at Broward described enduring vicious and relentless anti-gay harassment that pushed him to attempt suicide. “I don’t know what’s worse, this or death,” he said.

It is inexcusable that detained people must endure such conditions, but just as the U.S. criminal justice system witnessed the ascent of for-profit prisons and an explosion in the prison population that has only begun to diminish with sentencing reforms enacted in many states, immigration prisons are the new cash cow for the incarceration industry.

For decades, immigrant detention was a fraction of what it is today. The boom in incarcerating immigrants is driven in part by the private prison companies that detain the majority of noncitizens in the country. Localities contract with ICE to hold noncitizens – currently at an average daily rate of $280 per person. Some facilities, such as Glades, do the job for $81 a day or even less. This has encouraged a sprawling network of immigrant prisons.

These facilities are governed by various detention condition standards, and ICE fails to effectively enforce this patchwork of standards. This means that individuals in immigrant detention are often held in dehumanizing conditions that amount to harsh punishment while waiting for their immigration cases to be heard.

The Trump administration’s extreme anti-immigrant policies have only bolstered this system – perhaps best exemplified by two major private prison companies seeing their stock prices virtually double four months after Donald Trump’s election. Before the election, the Department of Homeland Security was considering moving away from using private prison companies altogether.

The people held in these facilities include an increasingly broad swath of noncitizens, as ICE has adopted a zero-tolerance policy that ignores circumstances such as long-time U.S. residence, serious health issues, and family connections to the United States in deciding who to detain. In ICE’s own words from a 2018 Department of Homeland Security report: “There is no category of [unauthorized immigrant] exempt from immigration enforcement.”

The policy shift is especially evident in Florida, where arrests of unauthorized immigrants without criminal records are seven times the number of such arrests in the previous administration and more than twice the national average, according to a 2019 review by the Tampa Bay Times.

Despite treatment that is inarguably punitive, people held in immigrant prisons are considered to be in civil proceedings and do not receive a lawyer at government expense. This means many detained people don’t have an advocate when they encounter these conditions.

South Florida, which is home to a large immigrant population that has enriched the region’s culture, is a significant state within our nation’s immigrant prison network. The failures at the four facilities examined in this report highlight more than a local problem. South Florida is indicative of failures throughout the nation’s bloated immigrant prison system – failures that can only be corrected by turning to more cost-effective and humane alternatives to incarceration, shrinking the number of people detained, and strictly enforcing constitutional standards to protect the lives of the people locked away within this system.

More detailed recommendations are offered at the end of this report.

Overview

The United States has the largest immigration incarceration system in the world. Immigrant incarceration, known euphemistically as “immigrant detention,” is a system in which noncitizens are detained in prison-like settings while they wait for deportation or for the immigration court to decide their cases. Despite the United States having the world’s largest immigrant incarceration system, it remains largely invisible to the public.

The nature and scale of immigrant detention today is a relatively new phenomenon. The first detention center in the United States, Ellis Island Immigration Station, opened in 1892 and held new immigrants between a few days and several weeks.1 In 1893, Congress passed the first law requiring the detention of anyone not entitled to admission into the United States.2 Three years later, the Supreme Court concluded in Wong Wing v. United States that immigrants could be detained for the purpose of forcible removal from the country.3

While it may seem inconceivable now, the United States largely did not detain immigrants in the past. In 1954, the attorney general announced that in “all but a few cases,” those whose removal was pending would no longer be detained.4 That same year, Ellis Island closed.5 From 1952 to 1983, only about 30 people nationwide were in immigrant detention on any given day.6 In the 1980s, the Reagan administration embraced concepts of enforcement, detention, and deportation, which set the tone for every administration thereafter.7

Immigrant incarceration as we know it today really began in 1996. The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act and the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act enacted that year fundamentally reshaped immigration policy. They established mandatory detention, created programs entangling police with deportation efforts, and expanded categories of crimes for which noncitizens can be detained and removed. As a result, the average daily population (ADP) of noncitizen detained individuals nearly tripled from 1995 to 2001.8 It has only grown since.

Immigrant incarceration today

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) is the branch of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) charged with enforcement and the operation of immigrant detention facilities that are, in effect, punitive. Most detention facilities are repurposed prisons, and many are situated in actual jails and operated by local sheriffs; others may be operated by private prison corporations.

This is antithetical to the idea of “civil” detention, which should not be punitive. By choosing to detain immigrants, ICE has the legal obligation to adequately care for them by providing necessities like food, shelter, clothing, toiletries, recreation, access to information to fight their immigration cases, contact with loved ones and attorneys, and medical and mental health care. Immigrants in detention, however, are routinely denied many of these basic rights.

Immigrant incarceration is, in many ways, indistinguishable from prison. This includes wearing prison uniforms, going outside only if and when the facility permits, and enduring up to four “counts” per day, when all movement in the facility is frozen so authorities can count the detained individuals.

Those detained report feeling stripped of any sense of personhood or agency, having to follow strict protocols. “There is no freedom here,” says Joseph H. who expresses frustration about being locked away in segregation for nearly 24 hours a day.9

For those in active removal proceedings, court takes place inside the detention facility, either in person or via video-teleconferencing. The Department of Justice’s Executive Office of Immigration Review (EOIR) operates an administrative court system under the authority of the Office of the Attorney General. Unlike criminal courts, those in immigration court have no right to an attorney provided by the government and can have one only if they can afford to pay for one on their own.10

The length of time spent in detention varies widely. Currently, the average length of stay for detained immigrants is a little over 54.7 days.11

Immigration detention standards

ICE has a patchwork of standards governing the conditions of confinement in immigrant detention, which are based on jail and prison standards. They govern matters such as the provision of medical care, use of force, and protection against sexual assaults.

It is often difficult to determine what standards apply to any particular facility. Currently, ICE has three different sets of standards: the 2000 National Detention Standards and the 2008 and 2011 Performance Based National Detention Standards.

ICE’s standards are not codified in law. Instead, the facilities are contractually obligated to follow whichever ICE detention standards are listed in their contracts. However, only 65 percent of detention facilities have one of these three standards in their contracts.12 In the South Florida facilities, Glades County Detention Center (Glades) still applies the 2000 standards, and Monroe County Detention Center (Monroe) uses the 2008 standards. Only Krome Service Processing Center (Krome) and Broward Transitional Center (Broward) operate under the most recent detention standards.

ICE currently uses two methods to inspect its detention facilities. It pays a private company, the Nakamoto Group, and relies on its Office of Detention Oversight. In addition, ICE has a Detention Monitoring Program for ICE staff onsite at detention facilities to monitor compliance with detention standards. These oversight mechanisms, however, are little more than a checked box. The DHS's Office of Inspector General (OIG) recently found that none of the mechanisms ICE employs to oversee its facilities adequately correct systemic deficiencies or ensure consistent compliance with detention standards.13

The lack of transparency and accountability allows substandard facilities to continue operating with impunity. ICE rarely uses financial penalties or legal mechanisms to ensure a facility’s compliance with its standards.14 Instead, ICE routinely issues waivers to facilities with inadequate conditions, effectively undermining the standards. And in the case of a facility managed by a private prison company, potentially allowing a possible contract violation by the company.15

ICE’s waiver process has no formal procedures.16 DHS’ Office of Inspector General analyzed the 68 waiver requests from September 2016 to July 2018 and found that ICE approved 96 percent of them, including waivers for safety and security standards.17

Financial Incentives in Immigrant Detention

The harms of prison privatization are widely known. These harms are magnified in immigrant detention, where private prison companies operate most immigrant detention facilities. In November 2017, over 71 percent of detained individuals were held in private prisons owned and operated by GEO Group and CoreCivic.18

Not only do private prison corporations profit off incarceration, they have influenced immigration policy by spending millions on campaign contributions and lobbying to expand incarceration and enforcement, particularly after the Obama administration announced in August 2016 it would scale back the use of private prisons.19

Just months after the announcement, however, Donald Trump was elected president and the stocks for both CoreCivic and GEO skyrocketed, reviving a shrinking industry.20 In 2017, the year the Trump administration reversed the decision to phase out federal contracts with private prisons, GEO spent $1.7 million on lobbying – over 70 percent more than the previous year. It also moved its annual conference to the Trump National Doral Golf Club near Miami.21

Contracts with private companies can encourage ICE to fill empty detention beds. A prime example is guaranteed minimums in ICE contracts — provisions that obligate ICE to pay for a minimum number of immigration detention beds at specific facilities and incentivize the agency to fill those beds.22

Private companies, in addition to operating their own facilities, often manage contracts, provide services, or otherwise support publicly owned facilities. They may provide telephone, food, and medical services, to name a few. In South Florida, one of the four facilities, Broward, is owned by GEO. The other three facilities – Krome, Monroe and Glades – are publicly owned but rely heavily on private correctional services.

Growing numbers of people in detention

The number of people incarcerated by ICE hit a record high in 2018 and seemingly hits a new peak every year.23 The amount the federal government spends on immigration enforcement exceeds funding for all principal federal law enforcement agencies combined.24 ICE detained over 55,000 people in August 2019, despite Congress authorizing funds for only 45,000 detention beds.25 This is up from 38,000 beds in 2017.

There is no indication that ICE’s expanding appetite for incarceration will stop anytime soon – the agency is currently seeking funding for 54,000 beds.26 In fiscal year 2018, 396,448 people were booked into ICE custody, a 22.5 percent increase from the year before.27

Entering ICE custody

People enter ICE custody in different ways. One of the most common is through an ICE detainer, also known as an ICE hold. Detainers are ICE-issued requests to local law enforcement to not release – or “hold” – an individual after completing the terms of that person’s arrest because ICE believes the arrested individual may be deportable.

In 2018, ICE’s Miami field office had the fastest growth in arrests for the second year in a row.28 The vast majority of ICE detainers are issued for people charged with low-level infractions, including many for traffic offenses.29 Importantly, detainers come at a substantial cost and risk of legal liability to the localities that enforce them. Police enforcing ICE detainers are detaining people without probable cause that they committed crimes, in violation of the Fourth Amendment. ICE also does not subsidize the costs of the extended detention.30 In 2017, for example, Miami-Dade County’s complicity with ICE detainers cost taxpayers $12.5 million, despite Mayor Carlos Gimenez’s claim that complying with detainers would save the county money.31 The county is on track to spend $13.6 million annually on enforcing ICE detainers.32

Immigration and local law enforcement

Local police are entangled in the enforcement of federal immigration law through a number of programs in Florida, all of which are deeply problematic. They raise constitutional questions, foster racial profiling, create unfunded mandates, and chill immigrant communities from reaching out to local law enforcement to report actual crimes.

SB 168 – In June 2019, Florida enacted Senate Bill 168 (SB 168), banning sanctuary cities in Florida. SB 168 requires state and local governments and law enforcement agencies to assist federal officials in enforcing immigration laws, including honoring ICE detainers.33 The law is currently being challenged in court as unconstitutional.34 It has also been criticized for its devastating impact on immigrant communities and law enforcement resources in Florida.

Secure Communities – Under this program individuals who are arrested have their fingerprints sent to ICE, which issues detainers requesting the locality hold certain people. Billed as a program targeting only the worst of the worst, it has a history of sweeping up people with minor offenses and exposing localities to lawsuits.

Basic Ordering Agreements – In 2018, ICE devised the use of Basic Ordering Agreements (BOAs), a supply order form from the federal government, to order immigrants in detention from local jails in an attempt to convert detention in the jail into ICE detention and somehow circumvent the constitutional requirement that police have probable cause that a person has committed a crime before detaining the individual.35 ICE rolled them out in Florida, where, as of August 2019, 46 counties – including Monroe County –have BOAs. But they are no shield for liability. The Monroe County sheriff is embroiled in a lawsuit by a U.S. citizen wrongfully detained and nearly deported despite the sheriff’s use of a BOA.36

287(g) – Under this program, local law enforcement are deputized to enforce federal immigration law. Five counties in Florida have 287(g) jail enforcement agreements in place,37 and the Florida Department of Corrections has also applied for one.38 In practice, these agreements have promoted racial profiling. They also have undermined law enforcement’s ability to solve crimes by discouraging immigrants from reaching out to the police and cost localities millions not reimbursed by ICE.

Warrant Service Officer Program – In May 2019, ICE launched the Warrant Service Officer (WSO) program, which enables deputies to serve administrative warrants and arrest immigrants on ICE’s behalf after eight hours of training.39 As of August 2019, 57 counties in Florida participate in the WSO program,40 which is basically 287(g)-lite and suffers from the same problems.

Types of detention facilities and contracts

Aside from its entanglements with local law enforcement, ICE also apprehends people through immigration raids, at the airport after Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) denies admission, outside of courthouses, at probation appointments, on buses, in workplaces, and seemingly random arrests in public.

ICE uses three types of facilities to detain adults. It owns facilities, called service processing centers (SPCs). ICE also contracts with private companies that own and operate privately owned facilities, called contract detention facilities (CDFs). In addition, ICE uses inter-governmental service agreements (IGSAs) to contract with local jails and state prisons – whether operated by public entities or by private prison companies – to detain noncitizens. Some IGSA facilities hold only individuals detained by ICE while others also hold people in criminal custody. Although an IGSA facility itself is publicly owned, many of these local and state-run facilities subcontract services, such as telephone, medical, and commissary services, to private companies.

South Florida has all three types of facilities. Krome is an ICE-owned facility. Broward is a contract detention facility owned and operated by GEO, ICE’s largest contractor. GEO holds more than $400 million in contracts with ICE.41 Monroe and Glades are both county jails that have IGSAs with ICE.

Immigrant Detention is Prison

There is virtually no difference between conditions of confinement for those detained by ICE and individuals in criminal custody. Despite immigration detention ostensibly being civil detention and subject to different legal standards and protections than criminal custody, detained individuals are placed in identical environments – often in the same facility.

A 2016 report by DHS’s Homeland Security Advisory Council recognized that ICE has not sufficiently created a civil model, which is meant to have “greater freedom of movement, expanded opportunities to retain personal property including clothing, enhanced recreational opportunities,”42 among other distinctions. None of those characteristics are present in any of the South Florida detention facilities.

For jails and private prisons, the same contractors who manage immigrant detention facilities also manage the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) facilities and state prisons, further blurring the already murky distinction between civil detention and criminal punishment. Detention facilities often have the same guards, the same protocols, the same types of housing, and the same sorts of programming found in prisons.

Like those in prison for criminal offenses, thousands of individuals detained by ICE are subject to segregation each year, often for arbitrary reasons, using the same disciplinary scale as the BOP. In Monroe, for example, Ron W. was sent to segregation for whistling, and Carlos G. was locked in his cell for protesting staff mistreatment of detained individuals.43

It is much the same situation in county jails, where detained individuals and those with criminal charges are both designated as “inmates” and housed together in the same dorms. At Glades, for example, the facility does not even use a detained person’s Alien Registration Number, but instead uses the jail number, similar to those in criminal custody. Those detained by ICE are also forced to wear uniforms – similar to those worn by the prisoners facing criminal charges – regardless of the nature of their custody. At Glades, for example, guards are often unable to differentiate between detained individuals and prisoners with criminal charges.

In other words, while different under the law, both ICE detention and criminal custody are effectively the same in practice – except those detained by ICE have fewer legal protections.

Inadequate Medical Care

ICE detention facilities nationwide are ridden with substandard medical care despite their constitutional and contractual obligations to provide adequate care. As the 2011 performance-based standards note: “Every facility shall directly or contractually provide its detainee population with…[m]edically necessary and appropriate medical, dental and mental health care and pharmaceutical services.”45

Immigrant detention facilities around the country, including in South Florida, routinely fall short, as there is little to no federal oversight to hold facilities accountable. South Florida detention facilities frequently conduct inadequate health screenings, rely on untrained medical care providers and provide insufficient staffing, and delay and deny care and medication. What’s more, the surge of the immigrant detention population without a corresponding increase in medical staff means that medical care in immigrant detention centers will only continue to worsen.46

ICE detention standards

Immigrant detention facilities all have contractual obligations to provide adequate health care, although the contracts adopt varying detention standards. For example, ICE detention standards did not explicitly address women’s health care (including prenatal and maternal health care), health care for transgender detained individuals, and sexual assault prevention and intervention policies until the 2011 standards.47

As a result, facilities using earlier standards, such as Glades and Monroe, have medical policies and procedures that put vulnerable populations in detention at risk because the outdated standards don’t address their needs.

Lack of Language Access

The ICE standards also require language assistance be available to individuals with limited English proficiency during medical visits and to provide meaningful access to programs and services. Detention facilities in South Florida, however, do not consistently apply this standard in violation of existing federal law,48 often leaving detained individuals unable to obtain effective medical care because they cannot meaningfully communicate.

At Krome, a detained person explained that interpreters are never used in the pill line, and that in the medical care unit, Krome “sometimes use an interpreter and they sometimes don’t,” resulting in inconsistent care.49

Transportation

Inadequate medical treatment starts at the beginning of a person’s detention – the transfer of an individual to the facility. Many people told us they did not have access to their medication during transport – a journey that can take anywhere from six hours to two days, based on our interviews.

While in transit to Krome, Julio F. reported not getting his HIV medication, a dangerous lapse, as the disease can manifest after missing one dosage.50 Another man with diabetes reported not receiving his insulin for two days while in transit to Monroe.51 ICE transportation can have devastating consequences on individuals with serious or chronic issues if they cannot access their medications.

Screenings

Once individuals are brought to the facility, the physical, dental, and mental health screenings conducted at each facility routinely fail to identify chronic medical conditions, resulting in long delays of proper medications and treatment.

Rowan D. is an example of an individual who was not screened properly and, as a result, is left particularly vulnerable to abuse.52 Although never diagnosed, he reported he has a cognitive disability that medical staff failed to identify during screening. When Rowan arrived at Glades, he said he expressed concern that he was in danger in the general population. Glades staff initially agreed, but rather than transferring or releasing him, placed him in medical confinement for four nights.

Later, Rowan says he was returned to the general population without additional services or monitoring. Rowan, without a lawyer or help from medical or mental health staff, has had to adjust to incarceration on his own. He subsequently reported hallucinations, paranoia, and delusions that continued to escalate without proper treatment or attention.

Delay of medication

After arriving at the facility and being medically screened, it can take another few days before receiving proper medication. Often, the medical staff replaces people’s medication with a cheaper substitute without consulting the individual. This can be alarming for individuals, especially those with sensitive health issues that need constant attention. During our tour of Krome, a medical staffer told us that “high-tech medication won’t be available when they are deported so we give them low-end medication.”53

Inadequate dental care

Dental care is lacking, leaving detained individuals in pain and at risk for medical complications. Detention standards outline that detained individuals must undergo a dental screening within 12 hours of arrival. Out of 104 individuals that the SPLC and AI Justice surveyed across South Florida detention centers, only 22 reported receiving a dental screening within 12 hours of arrival.

Even when detained individuals are screened, they do not receive preventative care like dental cleanings or procedures like permanent fillings until they have been detained six months. Dental care is otherwise only provided to detained people in emergency situations determined by the severity of the pain.54

In practice, detained individuals told us that the emergency dental treatment provided is ibuprofen. Individuals who request emergency dental services for excruciating pain caused by cavities, broken fillings, or infected molars are told that there is nothing more that can be done for them until they reach the six-month threshold.

This means living with severe pain that can affect their ability to eat, drink, and sleep. Antonio R., a detained individual at Broward, described having such a severe infection in his molar that not only did he have to skip meals, but his vision was impaired.55 Antonio reported that he begged medical staff to extract the molar. Instead, he was given ibuprofen and sent back to his pod.

During the 2018-19 government shutdown, detained individuals had an even harder time accessing dental care. Juste R. was processed into Glades in December 2018.56 Within the month, Juste reported that he began to experience pain from a broken molar. He told us he submitted sick calls to staff only to be told: “We can’t do anything until the government opens.” When the government reopened in late January, Juste was prescribed pain medication but still was not taken to a dentist. When we interviewed him, he was still waiting for adequate care – almost four months later.

Delays and denials of dental care allegedly occur even in the case of dental emergencies. Rosbel R., a detained person at Broward, told us it took a month for him to see a dentist for molar pain.57 Whenever he placed sick calls, medical staff would tell him – in an apparent attempt to deter him from seeking dental care – that the dentist would only extract his teeth. When he finally received care, Rosbel said that his cavities were properly filled and sealed.

Sick calls

Detained individuals reported that requests for medical care commonly go ignored, forcing them to submit multiple sick calls and grievances to receive proper medical assistance. If they receive a response, detained individuals rarely meet with a doctor or receive proper care within the required 24- to 48-hour time frame. When a response is given within the timeframe, it is usually unhelpful.

Once individuals finally meet with a medical professional, typically a nurse, they are routinely given ibuprofen or Tylenol as a one-size-fits-all solution. It can take months of filling out grievances and sick calls to receive an X-ray or any sort of diagnostic testing, or to see a specialist off site.

Hospital care

Detained individuals report that if ICE deems a situation serious enough to warrant transferring a detained person to a hospital, he or she is handcuffed to the hospital bed – an uncomfortable and dehumanizing practice that is not conducive to the healing process.

Many individuals allege they are discharged from the hospital prematurely, making their recoveries more difficult at the detention facility. Antonio, for example, was struck over the head with handcuffs by another detained individual while being processed at Krome. He reported that he was rushed to Larkin Hospital where he was handcuffed to the bed as doctors stitched the gash on his head.58 He told us that after a couple hours, he was transferred back to Krome before recovering from the assault. Over a month later, Antonio said he still had not recovered from his concussion.

Chronic health conditions

Although ICE by statue can release individuals with severe medical conditions from detention,59 it fails to exercise that discretion even where it appears obviously warranted. Detained individuals with chronic medical conditions are at an increased risk of harm in ICE detention, where they do not receive adequate medical care. When asked how his diabetes was being treated at Monroe, Magdeleno M. responded, “I am sure I am going to die here.”60 Indeed, less than two months earlier, a man with a chronic condition died at Monroe after an apparent failure to receive proper medical care.61

Luis C. recalled an older Cuban gentleman with diabetes losing a finger while at Broward as a result of the substandard medical care.62 This incident caused a group of men to protest for better medical care. Luis told us that the leaders of the protest were removed from the facility before the next morning, including the man who lost his finger. They were either transferred or deported. Luis reports being too scared to complain or write grievances about his own medical issues because he does not want to be deported.

Individuals with chronic conditions at all four facilities reported great difficulty receiving medically necessary accommodations. For example, Luis requires a low cholesterol and low sodium diet because of his high blood pressure and HIV-positive status.63 The only dietary accommodation made by Broward is to substitute his desserts with an apple.

At Broward, Guillermo M. requested a special diet for his gastritis, an inflammation of the stomach that usually requires high-fiber, low-fat, and low-acidity foods.64 Guillermo reported that his request was denied. His condition worsened as a result. In the rare situations where individuals received a special diet, they reported the meal portions being much smaller, forcing them to spend their money on food at the commissary.

Detained individuals with chronic medical conditions report their biggest fear being that they will have a medical emergency and that the staff will not react with urgency. Carlos G. told us he submitted several requests to Monroe to keep his inhaler for his asthma in his cell – requests that were ignored or denied.65 One day, he had a severe asthma attack while in his cell. He was fortunately able to get the attention of another detained person who contacted a guard, after which it took one hour for the on-site nurse to arrive and provide his inhaler.

“I spent an hour thinking I was dying,” Carlos said. Every time he needs to use his inhaler, he has to go to the infirmary – a process that means hours often pass before he is able to use it.

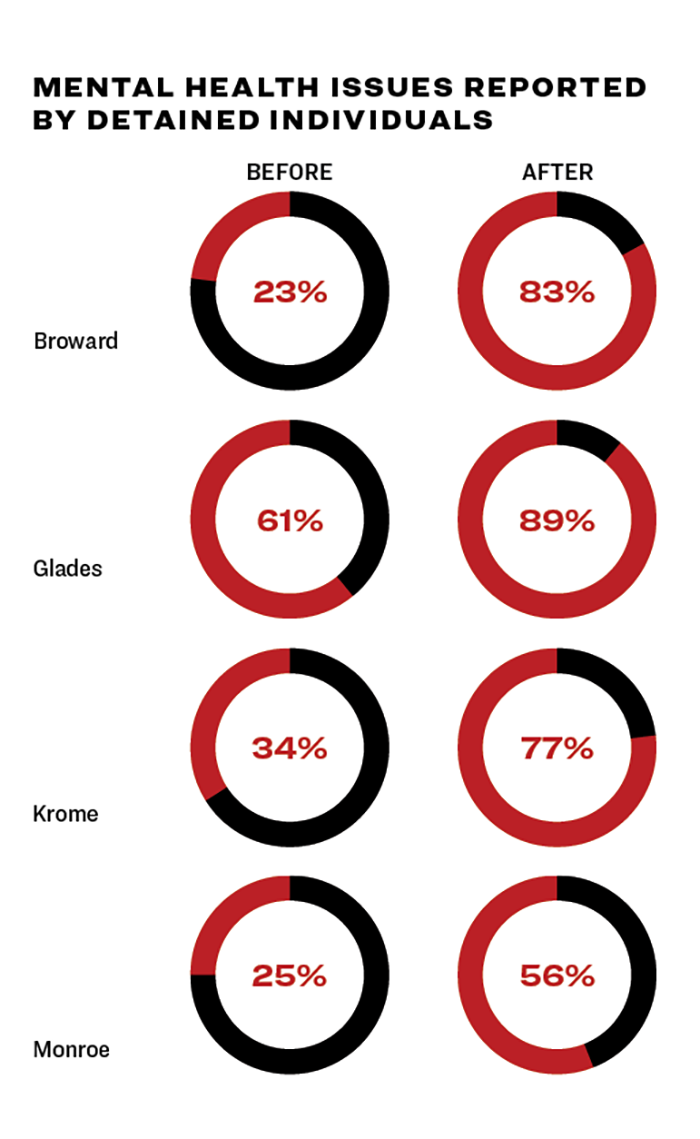

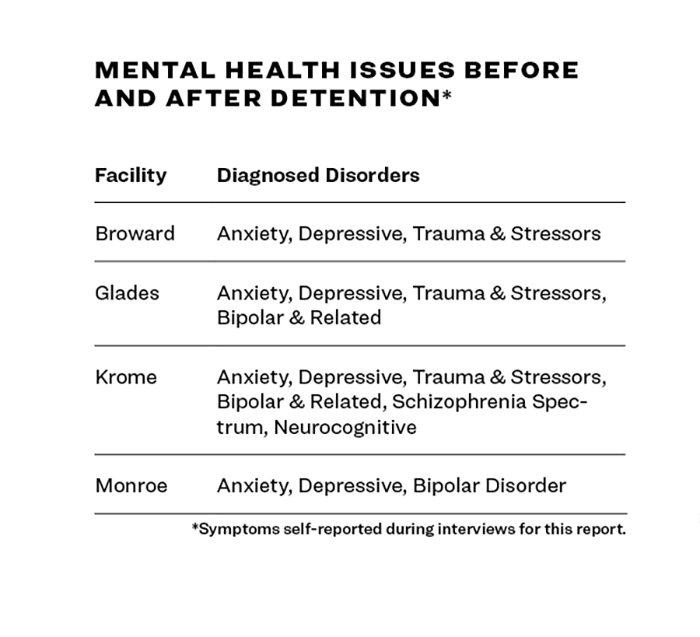

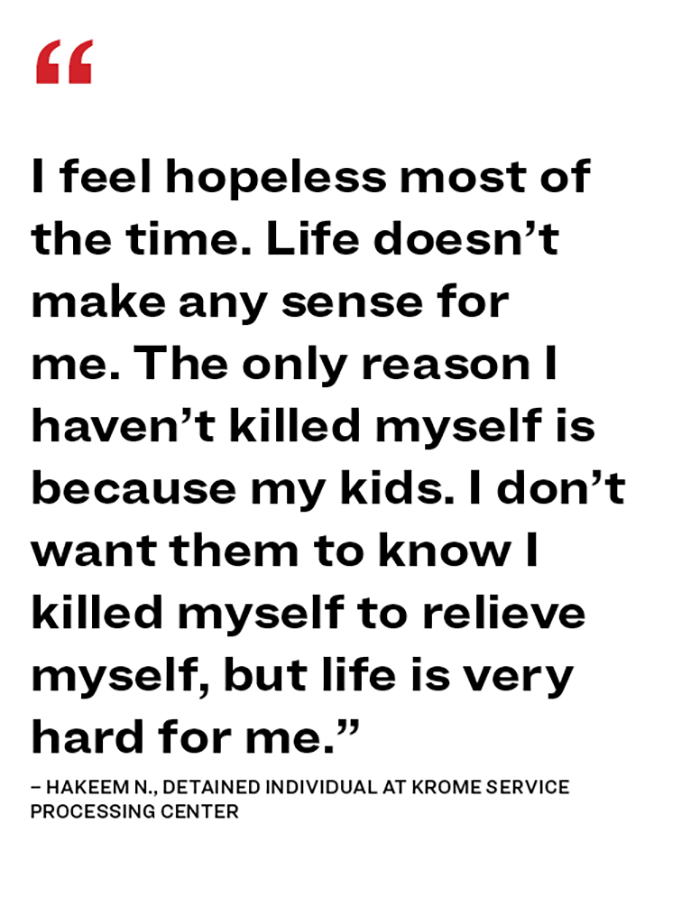

Inadequate Mental Health Care

As with medical care, ICE detention standards vary for mental health care. There is only brief mention of mental health care in the 2000 National Detention Standards, which call for an immediate mental health (as well as medical) screening for every new arrival. It also notes that the officer in charge will arrange for any specialized health care, apparently including mental health care. The 2008 and 2011 standards, on the other hand, specifically address mental health care, with concrete requirements. For example, these standards require that each facility have either an in-house or contracted mental health provider.

Our interviews confirm what ICE’s detention standards show – the level of mental health care an individual is able to access is largely contingent on where that person is detained. Lack of consistency is endemic within ICE facilities. Because of the pernicious nature of detention and the patchwork of standards ICE has in place, individuals in ICE custody are frequently unable to access necessary care. And if a person is transferred from one facility to another, there are often problems with continuity of care. Out of the four South Florida facilities, the one with the most comprehensive mental health care is Krome, although many detained individuals responding to our surveys nonetheless report deficient care at Krome.

Mental health impact of incarceration

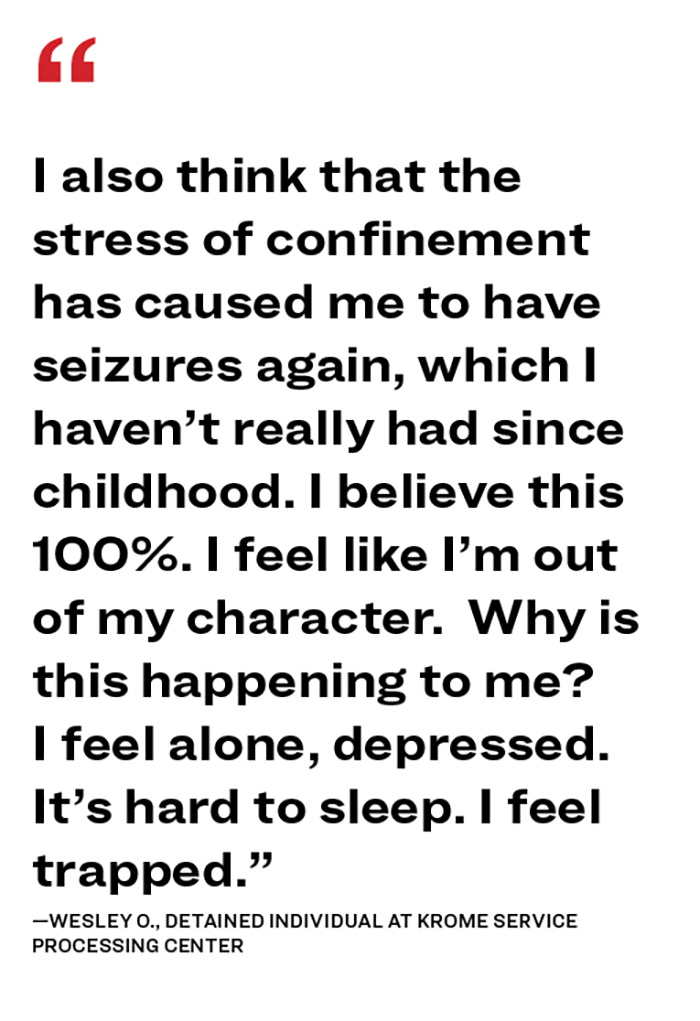

The stress and trauma of being incarcerated can exacerbate pre-existing mental health conditions or spark new mental health issues for a detained person. In addition, there is no fixed “sentence” for ICE custody. This means a detained individual grapples both with the uncertainty of whether he or she will avoid deportation along with the stress of not knowing how long he or she will be held in detention.

The isolation of immigrant detention, often in a remote facility and deprived of human touch, can be devastating.67 “Being a detainee will break you down,” said Erec V., a man detained at Krome.68 “I try my best to call home every day. That helps me, when I talk to my kids.”

Not everyone is able to speak with their loved ones as easily or consistently. Detained people commonly expressed that they had difficulty sleeping, lack of appetite, and a general sense of hopelessness.

“The hardest thing has been being separated from family and not being able to live life as free.” said Wesley O., a man detained at Krome.69 “It breaks you down mentally.”

Mental health care in south Florida facilities

The damaging consequences incarceration has on mental health are well-documented.70 Lack of adequate care is common in immigration detention, and South Florida facilities are no exception. During our interviews, common complaints from detained individuals included inadequate mental health treatment and replacement medication that is frequently not as effective as the original medication used by individuals before they were detained.

Different entities provide mental health services at the four Florida facilities: ICE Health Service Corps (IHSC) does so at Krome; GEO at Broward; Armor Correctional Health Services at Glades; and Correct Care Solutions at Monroe. ICE also uses local hospitals when the required treatment is beyond the facility’s capacity. During transport to local hospitals, as well as during their time at the hospital, individuals detained by ICE are shackled, a particularly inhumane practice for individuals with mental health issues.71

Each detention facility reported to us that when the facility detains an individual who has been taking medication, continuity of care is provided. Our interviews showed, however, that it can take over a month for an individual to receive “replacement medication” that may be different from what the individual was previously prescribed.

ICE claims its replacement medications are comparable, but detained individuals widely complained about their effectiveness. People with diagnosed mental health illnesses reported that they were not receiving proper care, largely because of the “replacement medication” and the brevity of meetings with care providers. At least two men diagnosed with schizophrenia said that their “replacement medication” is not working. Yet they understand they have few options: They must either take the replacement medication or receive nothing at all.

Telemedicine, the use of technologies like video-conferencing to provide long-distance health care, is increasingly common in ICE prisons, particularly in remote detention facilities. Telemedicine is no replacement for human interaction in mental health care, where personal contact and rapport are essential. Detained individuals shared their frustrations with the inability to establish a personal connection, and therefore a sense of trust, with a person in a screen. People also reported very brief sessions, where they are asked: “How are you feeling?” and “Have you thought about hurting yourself?” The counseling session typically ends after these questions are answered. The use of telephonic interpreters add another barrier to effective care.

ICE regularly detains people with mental health diagnoses. We encountered people with depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder. People who manifest symptoms of mental illness have more disciplinary infractions in immigrant detention and higher incidences of solitary confinement that can further damage mental health.72

“I don’t know if there is a counselor here,” said Carmen A., a woman detained at Broward.73 “But my friends have submitted grievances about [the lack] of mental health [services]. They have asked for help, help for women, hoping that the therapist will see them but nothing happens. We need help. We need support.”

Kitt U., another detained person, reported repeatedly trying to see a psychiatrist at Krome to modify his dosage.74 “I’ve seen everyone but him,” he said, expressing frustration that his replacement medication does not meet his needs compared to the medication he took pre-detention.

A common complaint was that individuals were overmedicated. Many people reported feeling that they had an impossible choice between receiving immediate treatment for their mental health conditions or remaining lucid enough to focus on their immigration cases.

“People who ask for help just get pills to go to sleep. I want to be conscious, I need to focus on my case,” said Bajardo T., a detained individual at Krome.75

Yazid D., a detained man at Krome, told us he started taking medication because he began speaking to himself, losing his memory, and sometimes did not know what he was doing.76 The medication he was given made him feel worse – he did not want to speak with anyone, suffered frequent headaches, and just wanted to be by himself, which scared him. He quickly asked to be taken off the medication.

Some detained people reported feeling a duty to look after those who are clearly not receiving needed care. Claudio O. reported that there is someone with a severe developmental disability in his pod at Krome.77 He is frustrated that ICE is keeping the man, who must wear diapers at night, in general population instead of the medical or behavioral health unit. Claudio shared that he and other people in the pod feel they must look after this person as ICE will not. As soon as this person wakes up in the morning, they help him by taking him to the bathroom, where they clean him.

Asylum-seekers & survivors of violence

Asylum-seekers and refugees are more vulnerable to mental health issues in detention due to their higher exposure to trauma. As one academic review of the impact of immigration detention on mental health noted: “In addition to pre-migration factors such as exposure to torture or human trafficking, post-migration factors, including prolonged asylum procedures, prohibition from working, poverty and poor housing are significantly associated with poor mental health.”78 They also are commonly associated with symptoms of emotional distress and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Likewise, some individuals incarcerated by ICE are survivors of sexual assault and domestic violence. Being under the strict control of a detention facility can retrigger trauma from past abuse and incidents of being under the control of another. As with asylum-seekers, incarceration often compounds the trauma of survivors of violence.

Ivette O., a transgender woman from Central America, reported harassment from guards at Broward.79 She said the bullying reminds her of the abuse she suffered back in her birth country. In one instance, a guard barred her from the line because she was running a couple of minutes late. She went without lunch that day. The experience reminded Ivette of being kicked out of her family home, going hungry, and begging for food from neighbors. Ivette said she regularly secludes herself in the bathroom and cries.

Krome has the most comprehensive unit of the four facilities but still falls short. At Glades, we heard reports of racist remarks and inappropriate legal advice dispensed with mental health treatment. Broward’s use of brief consultations via telemedicine diminishes any possible benefit from mental health treatment. At Monroe, the desperation and powerlessness was palpable during interviews with detained individuals. One individual reported that psychotropic drugs are regularly dispensed at Monroe without prescriptions because people are so depressed.80

As Carlos G. described it to us, “They treat us like inmates, but we’re not. I argue with them daily to say we are not inmates but detained people. They don’t care. They threaten us with handcuffs.”81

James J., another man detained at Monroe, succinctly described his experience: “I am just suffering.”82

Lack of Accommodation and Discrimination Against Individuals with Disabilities

In South Florida detention facilities, ICE and its contractors regularly fail to care for detained individuals with disabilities. Individuals are reportedly denied hearing, vision, and walking aids. The lack of accommodations unlawfully harms individuals with disabilities and discriminates against them.

Lack of effective communication

Under federal law, facilities must provide communication assistance to detained individuals with disabilities.83 Detention facilities in South Florida, however, fail to comply. There are no braille computers for individuals with vision impairment or meaningful forms of communication for those who are hard of hearing. Detention staff members are reportedly untrained and unwilling to help detained individuals with the appropriate accommodations.

For example, Miguel C., a deaf man at Krome, went six months without being able to communicate with staff and other people in detention.84 He was never provided an American Sign Language interpreter. As a result, he had to write in English to communicate, despite only having a second-grade education in the language. He otherwise had to use nonverbal signals. Because of ICE’s failure to ensure communication assistance, Miguel could not participate in medical appointments, mental health counseling, church, or other programs.

Lack of vision aids

Many detained individuals with vision impairments or near-blindness have their personal glasses confiscated and are not fitted for other glasses. ICE frequently denies individuals necessary eye surgeries such as cataract removal. It also regularly denies individuals their required vision aids.

Russell C. reported that he requested glasses for several months without any response.85 He finally received a response that ICE would not provide glasses to him because “he would not be in detention long enough.” Russell, who is detained at Krome, said he has been in ICE custody for over a year. He also requires cataract surgery, which has been denied. At Krome, another detained person who uses a wheelchair, was stripped of his glasses upon arrival. “I was denied eyeglasses because they said they could be used as a weapon,” he said.86

Bajardo T.’s glasses were broken during a search of the pod at Krome.87 Although he wanted to hold onto the broken glasses, guards allegedly told him that he had to throw them away because broken glass is a weapon. Two weeks later, a guard asked him for his broken glasses to exchange for a new pair. Once he explained what had happened, the officer responded: “Well, how am I supposed to replace them?” At the time of the interview – almost three weeks after his glasses were broken – he still had not received a replacement pair.

Lack of accommodations for limited mobility

While detained individuals often feel isolated in remote immigration prisons, detained individuals with limited mobility due to physical disabilities are even more isolated when detention facilities fail to accommodate them. Several people we interviewed reported violations of detention standards requiring equal access to programs, services, and activities.88

Some individuals, like Juan T., face obstacles in having the detention center even acknowledge their disabilities.89 Juan, 62, has multiple sclerosis and has repeatedly requested a wheelchair from Krome. He’s been denied because his disability has not been approved by officials. Without this approval, Juan also has been denied access to a shower with grab-bars and seats – forcing him to shower standing up, which is very difficult for him.

Even when accommodations are provided, they often fall short. At Monroe, for example, Carlos G. said the shower stall for disabled detained individuals is too narrow for his wheelchair to fit.90 With no alternative, Carlos musters his strength to hold on to the shower rod in the stall with one hand and uses the other to wash himself.

Russell C., who is detained at Krome, has a wheelchair, but the facility is so overcrowded that he cannot use his wheelchair to move around the dorm, where makeshift cots cover the floor.91 Instead, he must fold up the wheelchair and lean on the handlebars to get around. ICE’s decision to house mobility-impaired people at facilities in which they cannot move around discriminates against them on the basis of their disabilities.

Solitary Confinement

Solitary confinement or “segregation” – the term ICE uses – is the practice of placing someone in a cell either by him or herself or shared with another individual for nearly 24 hours per day. Almost all other human contact is cut off, including all daily “privileges” such as phone calls to loved ones. Solitary confinement is managed according to ICE’s Segregation Directive, which is meant to complement requirements in the 2000, 2008 and 2011 detention standards.92

The use of solitary confinement in ICE incarceration, however, is in direct opposition to the “civil” nature of immigration detention, which is not supposed to be punitive. The harm caused by such isolation includes increased anxiety, depression, self-harm, and suicidal ideation. The United Nations special rapporteur on torture has called on all countries to ban the use of solitary confinement for punishment and cautioned that it be used in only in exceptional circumstances.93

ICE uses segregation for both punitive and non-punitive purposes. Administrative segregation is ostensibly a “non-punitive” separation from general population, authorized by supervisory detention officials to ensure the safety of the detained person. Disciplinary segregation is meant to be punitive. Disciplinary segregation policy requires a hearing before a panel of detention officers to determine if segregation is warranted and, if so, for how long. While awaiting this hearing, which can take several days, an individual is usually still isolated in “administrative” custody.

Three of the four South Florida facilities regularly use isolation units: Monroe, Krome and Glades.94 Broward does not, although individuals are often threatened with transfer to other detention centers for disciplinary infractions. Under ICE policy, “[p]lacement of detained individuals in segregated housing is a serious step that requires careful consideration of alternatives. Placement in segregation should occur only when necessary and in compliance with applicable detention standards.”95

However, we heard from detained people that threats of isolation, or “the box,” as detained individuals commonly refer to it, are made regularly. Of the people we surveyed at facilities using isolation, more than one in five had been in or were currently in confinement – a striking number for a procedure that requires “careful consideration of alternatives.” This reflects a pattern of overusing segregation in immigrant prison nationwide.96

People reported frequent isolation for arbitrary lengths of time. For example, Ron W. told us he was sentenced to disciplinary segregation for 16 days in Monroe, just for singing Bob Marley’s “Redemption Song” in the pill line.97 After singing the song, which includes the lyric, “Won’t you help to sing these songs of freedom?” he was charged with “obstructing the pill line.” Ron did not understand why he was in isolation until he heard “obstruction” at his disciplinary hearing. And it wasn’t until he had spent three days in isolation that he received paperwork informing him of the length of his segregation – 16 days.

When he was sent to isolation, he reported that a nurse told officers, “You can’t take this man.” She cited his elevated blood pressure, but was ignored. His segregation cell was covered in so much mildew that he developed a fungus on his skin and scalp and had to cut off his hair. The lotion Ron was given to treat the fungus burned his scalp, leaving it red and raw, and requiring more medication. During his 16 days in isolation, Ron was only allowed two showers.

In another instance, Akhil A., a Somali man at Krome, said he was sent to isolation for five or six days just for having an extra water bottle.98 Akhil, who is accustomed to using a bidet, used the extra bottle to clean himself after using the bathrooms at Krome, which do not have bidets. When guards discovered Akhil had two water bottles (one for drinking and the other for cleaning himself), he was written up and sent to isolation.

We also frequently heard of ICE punishing people with mental health symptoms by sending them to isolation, often based on the behavioral manifestations of their mental health conditions. Isolation, however, can worsen symptoms or undermine medical care the person was previously receiving.99

ICE allegedly fails in many cases to identify behavior symptomatic of a mental health condition and instead sends individuals to isolation. For instance, Junipero V., who has a history of suicidal ideation, self-harm, anxiety and panic attacks, recalled a panic attack while at Monroe. He described the attack as sending him into “crisis mode.” In lieu of mental health treatment, the staff placed him in the “observation room” – a room that mimics segregation except that it is in the medical unit. He spent an entire day alone in the room – naked, except for a green smock. He was provided no therapy, books, or television. He calmed himself down to get out of the observation room as quickly as possible.

We also found that isolation is used for retaliation. At Monroe, Carlos G. uses a wheelchair due to an injury from a motorcycle accident.100 When Carlos spoke out against the way the guards treated him and others in ICE custody, two officers pushed his wheelchair into his cell and did not let him out for any reason for two days. A nurse brought his food and medicine, and looked inside the cell through the small window on the door. Carlos was not told how long he would be locked in his cell.

By confining Carlos to the cell and not taking him to the segregation unit, the facility circumvented the few procedural rights – a hearing and documentation – that people in isolation receive. “I didn’t know how long I’d be in there for,” he said. “I panicked. You go crazy in [those] walls. I didn’t want to start nothing. I am trying to get out. I got a lot to lose.”

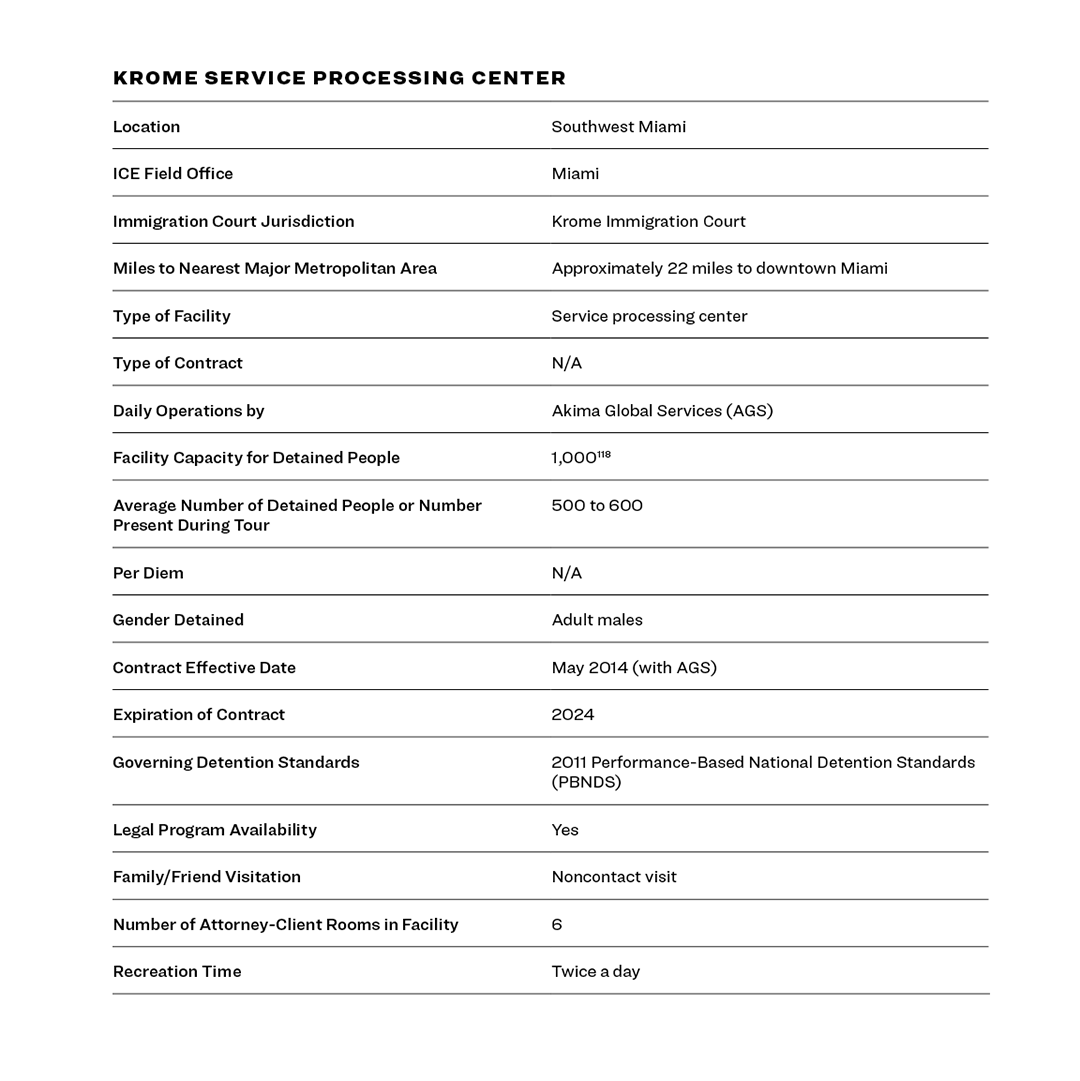

Krome Service Processing Cener, Miami, FLA.

Krome Service Processing Center was originally built in 1965 as a Cold War-era air defense base.101 In 1980, thousands of Cubans, by way of the Mariel Boatlift, and Haitians fleeing the horrors of Jean-Claude Duvalier’s regime began to arrive on Florida’s shores.102 Krome was repurposed as a detention and refugee processing camp, comprising two tents housing 2,000 individuals – one for Haitians and the other for Cubans.103 Krome’s mistreatment of the people detained there, which included widespread abuse and sexual violence, was documented for decades.104 Largely because of those findings, it was converted to a men-only facility in 2000.

ICE now maintains that Krome is a “gold standard” for detention facilities. It has six pods for general population, a medical unit, a segregation unit, and a transitional unit for those with “behavioral” issues. Akima Global Services (AGS) is contracted through 2024 to handle the daily operations of the facility, including food services and funds processing for detained individuals. Included in this contract is a mandatory minimum of 450 occupied beds.105 ICE Health Service Corps provides medical services.

Upon request, ICE was unable to provide the maximum capacity of the facility. According to the AGS website, Krome detains an average of 600 detained individuals. Since 2006, the population has fluctuated between 550 and 875 people.106

The facility contains three courtrooms, six attorney-client (contact) visitation rooms, and 26 non-contact visitation booths. All non-legal visitation at Krome is noncontact to “minimize contraband.”107 There are typically three judges who regularly hear cases at Krome. Judges at Krome hear cases of those detained in the facility and also cases from Glades and Monroe. Depending on the judge, the hearings for those detained in remote county jails can occur either through video teleconferencing or in person at Krome.

Within each of the six pods are 65 beds. Krome also has a 30-bed medical unit, of which 10 beds are reserved for people with mental health issues. The medical unit also includes an intensive care unit, an observation room, and a medical isolation unit. The facility has a 30-bed transitional unit that, per ICE, is the only one of its kind.

A detained person is subject to pat-downs if he or she goes anywhere inside the facility, such as walking from the pod to the dining hall. There is a segregation unit containing seven cells that can hold a total of 14 people. Krome also has recreation areas and a law library with 15 computers. People are allowed two hours a day in the library with a prior request and extensions on a case-by-case basis.

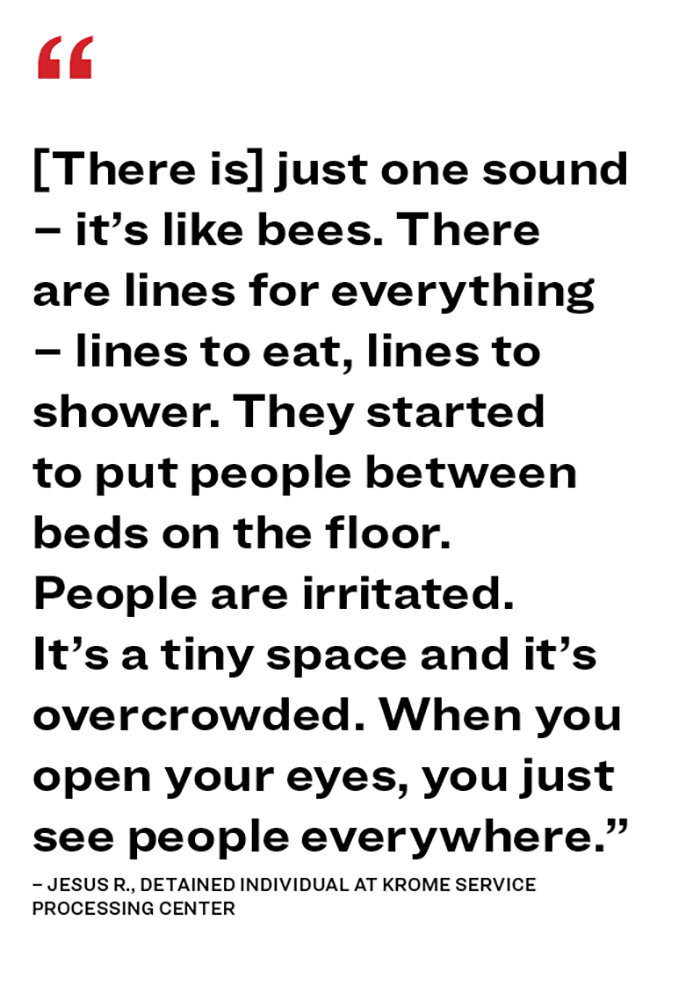

Overcrowding

A primary complaint at Krome is severe overcrowding. While individual pod capacity is supposed to be about 65, some detained individuals estimate there are 100 or more people in their pods, a level that, we were told by a detained person, feels “dangerously overcrowded.”108 In addition to approximately 65 beds in each pod, the facility has since added military-style cots, or “stackable beds,” between bunk beds, next to the phones, between chairs in the TV area, and even by the restrooms and in front of the showers. People interviewed for this report complained about back pain from sleeping on the cots, which lack mattresses or cushioning.

Individuals with physical disabilities often receive medical passes requiring them to be on a bottom bunk. Due to the severe overcrowding, individuals report fear that their passes will not be honored by detention staff. When Russell C. was sent to segregation for three days, he returned to his pod to learn that he lost his bottom bunk and would be forced to sleep in a temporary cot, despite using a wheelchair and having a bottom bunk medical pass.109 When he alerted ICE staff, he was reportedly told no bottom bunks were available, and he would have to wait until one was vacant. As far as navigating the overcrowded pod with his wheelchair, Russell reports having to collapse his wheelchair and lean his body on the handlebars to maneuver the narrow spaces.

This overcrowding also means long wait times for basic things.

Understandably, with 100 people in a 65-person pod, tensions are high. Detained individuals report fights over phones, the restroom, and even a mirror. “Too many people sleeping on the floor. Sometimes [we] have to watch our step to walk,” Idris S. said of his detention at Krome.110 For Muslims, engaging in daily prayers is difficult due to the cots taking up space in the pod previously used to kneel for prayer.

Overcrowding also creates sanitation and health issues. Germs spread more easily and the pod is harder to keep clean. “There are so many people and you can smell them,” Joseph H., a man detained at Krome, said.111

Access to Medical Care

ICE regards Krome as a model for medical care. Generally, when there is a person in a Florida facility who requires more extensive medical or mental health care, ICE transfers the individual to Krome. Despite this, people at Krome reportedly lack access to adequate medical care in part, because there are about 600 people detained there.

Many people told us that medical issues were not properly treated or not treated at all. “If you’re sick, you suffer here because this is not designed to deal with the illnesses people come with,” said Jesus R. “Because people are in the process of being deported, they neglect you because it’s likely you will leave within a few weeks.”112 He observed that medical treatment at Krome is “painfully slow.” He added: “I [would] literally have to drop dead for them to react.”

Santiago C., who had an untreated broken wrist, said he was only given ibuprofen for his pain, but no splint or cast to deal with the underlying injury.113 Juan T. had a kidney infection but went 20 days without antibiotics.114

Krome’s most recent inspection in February 2019 found its medical care deficient, as procedures require that sick calls be addressed twice a day, but inspectors found that it took two to eight days at Krome to triage a sick call.115 That much time can be a death sentence for someone with an acute or emergent condition.

Access to mental health care

ICE boasts that the Krome Behavioral Health Unit (KBHU) is the only one of its kind. It is a 30-bed transitional unit which offers several group therapy sessions a day and other support to those not stable enough to be in general population, but do not need to be housed in the medical unit.

People in the KBHU generally appreciated the services there. Getting into the unit, however, is allegedly a challenge for those who need it most. Detained people told us placement in the unit was used as a bargaining chip. Suicide attempts or placement in solitary confinement reportedly disqualify a person for the KBHU, a significant issue for detained people since segregation is overused at Krome. Akhil A., for example, said that even though he was repeatedly told he would benefit from being in the KBHU, after segregation, he was told he no longer qualified.116 This situation appears to feed a vicious cycle – detained individuals not receiving adequate mental health care are put in segregation for behavior resulting from their mental health issues, and placement in segregation disqualifies them appropriate mental health care at the KBHU.

Outside of the KBHU, people reportedly receive therapy less frequently. At the time we spoke with Joseph H., he was on suicide watch because he threatened to harm himself.117 Suicide watch means being placed in a rubber-walled room in an anti-suicide smock. There are no windows, except for one on the door for staff to supervise individuals. But aside from being under suicide watch, Joseph said he was not receiving mental health treatment.

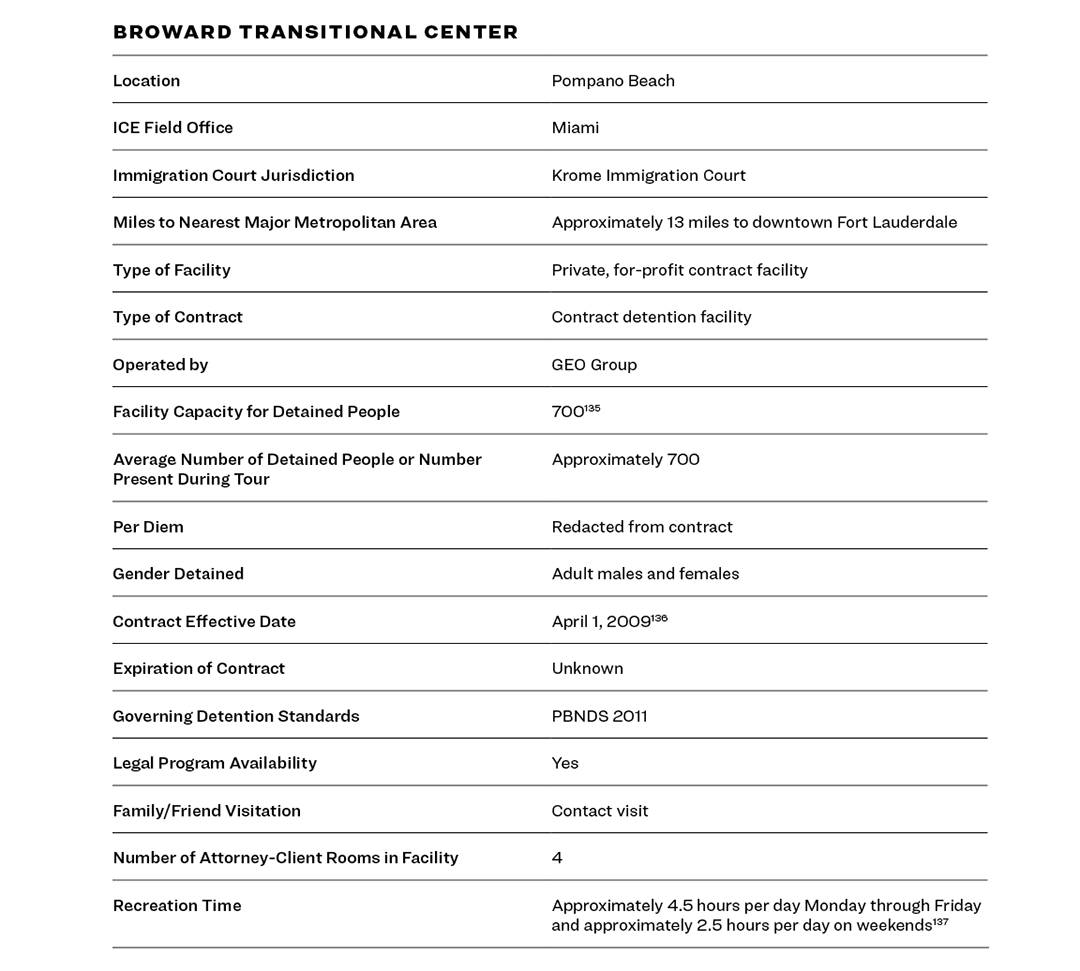

Broward Transitional Center, Pompano Beach, FLA.

The Broward Transitional Center, located in Pompano Beach, is operated by GEO. Broward first opened its doors in 2002, after being awarded an ICE contract to house level-one detained individuals (those considered noncriminal and low-security).119 These individuals, with no criminal history or only minor infractions, should not be detained at all.120

Among them are teens transferred in shackles out of the Office of Refugee Resettlement’s custody at 18, pregnant mothers, the elderly, asylum-seekers, and those who are active parts of their communities in the U.S. Included in ICE’s contract with GEO is a mandatory minimum of 500 beds, meaning that ICE will be contractually obligated to pay GEO for 500 beds even if the population at Broward dips below 500.121

Broward is often referred to as a “model” for immigrant detention centers, as its hotel layout allows for socialization during out-of-cell time. Immigrants in Broward are continually reminded by ICE officials and GEO staff how lucky they are to be there. As a result, many people at Broward say they do not submit sick calls and grievances, or otherwise call attention to themselves. However, as many detained individuals shared: “Aunque la jaula sea de oro no deja de ser prisión” (although the cage is golden, it is still a prison). In this case, the golden cage is across from the Pompano Beach landfill.

Since its opening, Broward has steadily grown in population capacity from 150 detained women to 700 detained women and men.122 There was renewed attention to substandard conditions at Broward, including poor medical and mental health care and abuse of prosecutorial discretion, with the release of a 2019 documentary highlighting these problems.123

Inadequate medical care

Deficiencies in medical care at Broward were documented years ago in a March 2012 inspection, including failures to transfer detained individuals to medical and mental health providers in a timely manner,124 a problem that persists today.

Many people in detention reported having to endure weeks and months of pain before receiving proper outside medical care. Although Broward responds to sick calls within 48 hours, individuals must make multiple requests to actually receive medical care, often delaying necessary interventions. Several individuals told us they were triaged by a nurse within the 48-hour window but were sent back to their rooms with only aspirin. People in detention are triaged but further medical attention is allegedly not provided in a timely fashion. One person shared: “I have to be on them all the time.”

Some individuals reported excruciating oral pain for weeks, limiting their ability to eat or drink. For example, Lionel S. told us he endured pain in his molars and bleeding gums for three months.125 After multiple sick calls, he was allegedly sent back to his room without dental care and instructed to buy mouthwash from the commissary – something out of his reach since he didn’t have any funds. He skipped every meal for a week because of dental pain. The only solution reportedly offered at Broward is extracting teeth that could otherwise be saved or receiving temporary fillings, which may fall out a few days later. What’s more, if he opted for an extraction, there is no follow-up treatment.

In another case, Raymond G. reportedly has been waiting over a month to see an orthopedic specialist for a sprained shoulder.126 While he has been waiting, he has only received painkillers, which he has used up – leaving him with no treatment. He has resorted to doing stretches he devised himself to retain mobility. Another man, Jose T., said he is losing mobility in his right arm after not receiving necessary physical therapy for a year despite his pleas to GEO staff.127

Other individuals who require outside medical care simply do not request it because they are concerned about the conditions they will endure for the medical appointment – leaving the facility requires being in three-point shackle restraints for hours with little or no food. For those with limited mobility or pain (physical or psychological), this process can exacerbate their conditions.

Inadequate mental health care

Detained individuals also reported a lack of mental health care in Broward. Many individuals were unaware that any mental health care was available. Broward currently has one English-speaking licensed social worker on staff who relies on translation services to address the needs of detained individuals, the majority of whom speak Spanish. Those who have used her services told us that over-the-phone translation therapy is ineffective as it does not capture the nuance of their communications to or from the social worker, resulting in little to no therapeutic relief.

Broward uses telemedicine for visits with psychiatrists, which is also inadequate, as it allegedly consists of 10-minute conversations about superficial issues through a screen, which hinders a therapeutic connection between doctor and patient and is mediated by an interpreter over the phone. Jose G. told us when he experienced his first suicidal thoughts at Broward, he asked for help and met with the licensed clinical social worker on staff.128 Because the interpreter was on the phone, Jose could only get in a couple of words at a time. He found it hard to open up with the interpreter cutting him off to translate. Jose reported that he never returned to therapy again and has since relied on his own devices to keep his suicidality at bay.

Inadequate mental health care at Broward is especially troubling as the facility primarily incarcerates individuals seeking asylum, who fled persecution in their home countries. Immigration detention conditions often have the effect of compounding their trauma as they are reminiscent of the same conditions migrants are fleeing – food scarcity, restricted freedoms and violence. 129

Luisa D. told us: “Regardless of where I end up, I think I’m going to need psychological help.”130 Florencio P., who is seeking asylum, says he is reminded of childhood trauma whenever detained individuals or guards raise their voices.131 At age seven and for years after, Florencio witnessed his father physically and verbally abusing his mother. He remembers yelling for help as a child. As more despair set in at that time, he began to experience suicidal ideation and symptoms of depression. When altercations occur at Broward, he reports that he begins to shake and holds back tears.

During a tour of Broward, we met Rodolfo V., who exhibited signs of suicidal ideation.132 After we flagged his case, ICE told us he would be seen by a mental health specialist immediately. The visit was only a 15 minute triage with a new dose of psychotropic medication. “Morale is killed here,” he said. “There is no hope here.” Rodolfo told us that although the telehealth psychiatrist asks about his case, he hates answering such questions, as he knows his problems are really because of Broward.

Because health care providers at Broward are GEO employees, there is an inherent conflict—individuals may be uncomfortable sharing intimate information about their well-being with the entity that is also the cause of so much of their suffering.

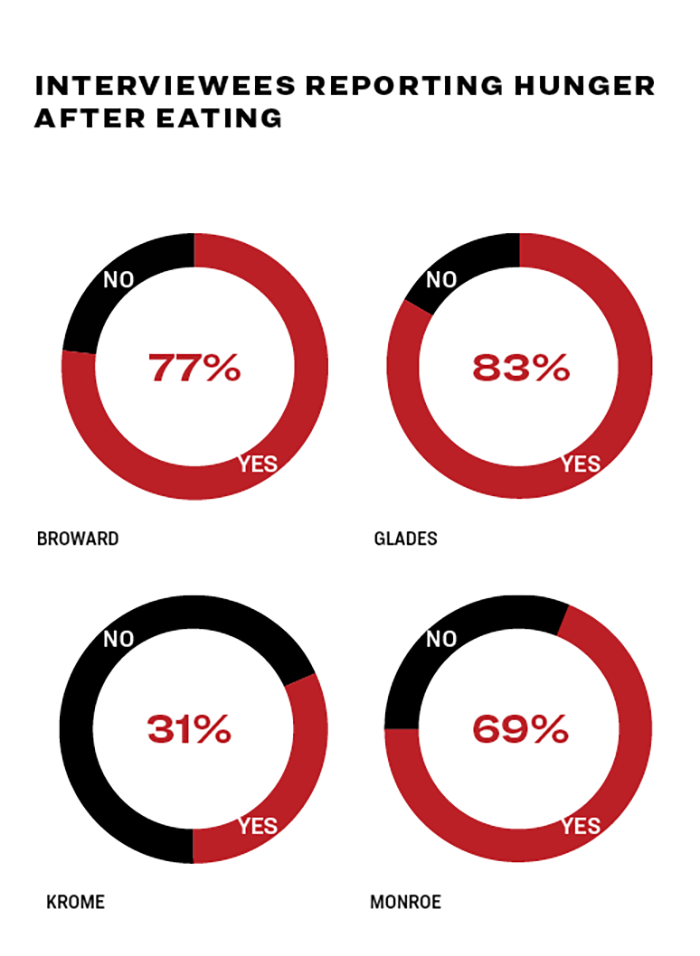

Insufficient water and food

Once a week at Broward, one person from each room will go without eating for over 12 hours to get cleaning supplies. The rotating cleaning schedule requires that a detained person stand in line for cleaning supplies, or risk getting the room reprimanded by detention staff for not cleaning. Because dinner is at 4 p.m. and breakfast is at 6 a.m., this means that on cleaning days, detained individuals must skip breakfast to clean and wait until lunch time for their next meals.

When Broward is at capacity, this schedule means 116 people out of 700 are going almost a full day without eating. Some Broward staff allegedly threaten detained people that failure to comply will result in transfer to another detention center. This is an ominous warning to individuals who are already being told to be grateful to be at Broward.

Access to drinking water is also limited. Broward provides no cups outside the dining hall. This forces people to purchase beverages from the commissary and save the container to pour water from the coolers available during recreation. Indigent people in detention rely on the charity of those with funds for these containers. Detained individuals are also limited to two 16-ounce bottles in their rooms; otherwise guards will confiscate all of their bottles and leave them with nothing to drink outside of the dining hall.

Unnecessary detention

As others have pointed out,133 there is no legitimate reason that Broward should continue operating. ICE has the discretion to parole individuals or release them on bond or on their own recognizance in order “to prioritize its resources, to detain and remove other individuals whom ICE deems to pose a greater risk to public safety or national security.”134

Because no one at Broward is subject to mandatory detention, every detained person should be eligible for parole or bond. As one detained person stated: “My case is everyone’s case.” Yet at Broward, ICE imprisons asylum-seekers and detained individuals with no violent criminal history and grants parole only with exorbitantly high bonds of $20,000 or $40,000 – in the rare instance ICE grants a bond.

After ICE’s decision to detain, immigration judges can still grant bond at an amount above the statutory minimum of $1,500. Such bonds are often denied, with judges often citing a driving without a license infraction as a threat to public safety. Out of 200 men surveyed at Broward, 47 percent were denied bond at the discretion of the court. Those same people are being told by GEO staff and ICE guards how lucky they are to be at Broward, even though, had they been detained at Krome, their bond would likely have been set at a lower amount, typically less than $10,000.

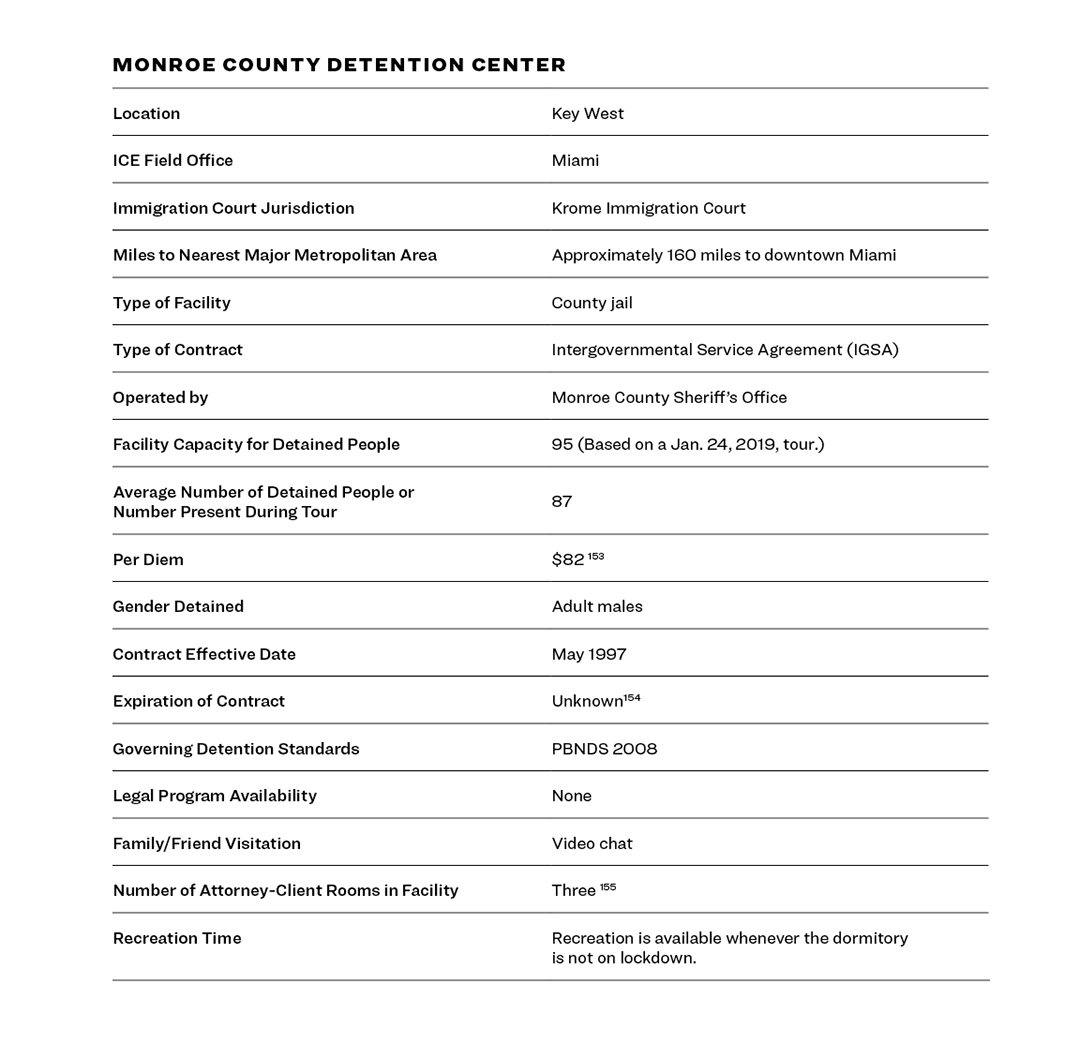

Monroe County Detention Center, Key West, FLA.

Monroe County Detention Center is in Key West, the southernmost tip of Florida. Located approximately 116 miles from Miami, and with only one highway in and out of the Keys, Monroe County acknowledges it is “time consuming and difficult” to get to the county.138 The remote location serves to isolate the individuals detained by ICE there.

Monroe is a county jail with a capacity to detain 700 individuals. Since 1997, Monroe has had an inter-governmental service agreement, renting detention space to ICE to temporarily house ICE-detained individuals.139 Under the IGSA, when a person finishes serving his or her time for local charges and an ICE detainer expires, the person is transferred within the jail into ICE custody.140 With the agreement, Monroe currently “rents out” a pod to ICE that can hold up to 95 individuals, although Monroe can expand the amount of detention space for ICE.

Isolation of detained individuals

Because of Monroe’s remote location and policies, detained individuals are almost completely isolated from friends, family, and immigration attorneys. Even in the rare event that a loved one travels to Key West to speak with a detained person, that individual cannot have a face-to-face visit, but must speak by video teleconference. In its detention standards, ICE notes that visitation ensures that detained individuals maintain morale and ties to their families and community.141 This is difficult to do through a medium that eliminates human contact and charges exorbitant fees for a service that was once free.

Detained individuals who set up video “visits” with loved ones remotely must pay $9.95 for a 25-minute chat or else rely on phone calls. In the pod, there are five phones for more than 80 people, creating long lines for the phone and no privacy for phone calls. The Monroe County Sheriff’s Office earns a 68 percent commission on these calls.142 These video visits and phone calls are reportedly out of reach for many detained individuals, especially when they first arrive at the facility before family members can deposit money in their accounts.

There are no community visitation programs at Monroe. Legal services organizations do not regularly conduct legal orientation or “Know Your Rights” presentations there. The law library is bleak, with outdated resources most detained individuals cannot understand because of the language barrier. One detained person described the library as “people fighting for their lives with terrible materials.”

More restrictive confinement than people in county custody

At Monroe, people detained by ICE are incarcerated in a county jail, which holds people with criminal charges or convictions. Those detained by ICE are essentially treated the same way despite being held in “civil detention.” The handbook provided to ICE detainees and people in county custody on criminal charges is the same and rarely distinguishes between them.

Junipero V., who was housed at Monroe and then Krome, emphasized that, unlike at Krome, which houses only people detained by ICE, the guards at Monroe do not understand the difference between detained people in ICE custody and those in county custody with criminal charges.143 He felt his detention was essentially a criminal punishment. In several respects, including the trustee program and access to recreation, people held by ICE at Monroe face worse conditions than people being held by the county on criminal charges.

Trustee program

People in county custody participate in the “voluntary work program,” through which they earn $1 a day for commissary and phone calls. While the program is deeply problematic and exploitative,144 people detained by ICE are allegedly paid even less for their work at Monroe. Detained people have a “Trustee” program, under which some are “trusted” to perform custodial duties for no pay. Instead, a detained person explained to us, they may receive extra food or have their cells unlocked during lockdowns.145

Inadequate recreation

Detained individuals’ recreation area is a rectangular courtyard adjacent to their housing unit. It is about a quarter of the size of a basketball court, with high walls and meshed wire overhead, allowing little sunlight inside. People in county custody have a comparable recreation area inside their pod, but also have access to a larger recreation area outside their pod, providing much more freedom of movement.

Because of the limited space in the ICE recreation area, not all people in ICE custody can use the recreation yard at the same time. The laundry exhaust fan also blows directly into this area making it a hot and uncomfortable environment for exercise. A man with asthma told us that in the recreation area, “your chest gets congested, you can’t breathe.”

Difficult Transportation for court hearings

Court hearings do not take place in Monroe, not even by video teleconference. Individuals are sent 146 miles away to Krome for immigration hearings. Every time detained people are transported, they are handcuffed in three-point restraints. The trip from Monroe to Krome lasts at least three and a half hours, meaning that people spend this long drive tightly restrained with no food, water, or bathroom breaks.