‘Never Give Up’: Iconic civil rights attorney Fred Gray Sr. receives Presidential Medal of Freedom

President Joe Biden today bestowed Montgomery, Alabama-born attorney Fred D. Gray Sr. with the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his titanic contributions to civil rights in the United States.

The country’s highest civilian honor acknowledges “an especially meritorious contribution to the security or national interests of the United States, world peace, cultural or other significant public or private endeavors.”

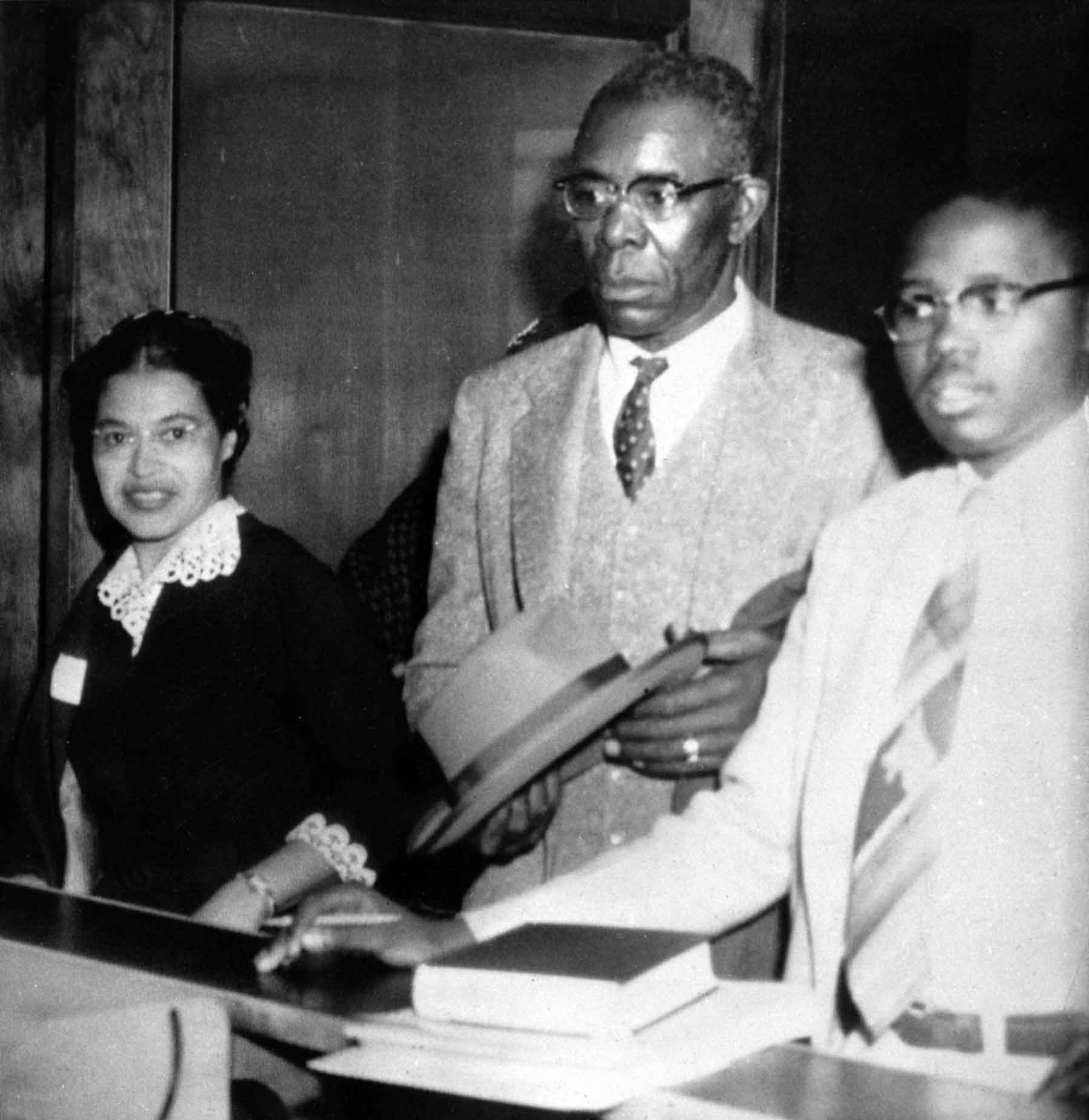

Once described by Martin Luther King Jr. as “the chief counsel for the protest movement,” Gray, 91, has a client list that reads like a Who’s Who of the civil rights era: King; John Lewis; Rosa Parks; the NAACP; Charles G. Gomillion, the lead plaintiff in a Supreme Court case that ruled gerrymandering unconstitutional; Vivian Malone and James Hood, the first two Black students to successfully enroll at the University of Alabama; and many others.

While Gray may not be a household name like Thurgood Marshall – the civil rights lawyer who became the first Black justice on the U.S. Supreme Court – over the course of Gray’s 65-year legal career he won many of the civil rights era’s signature legal cases, altering the national landscape not just for Black people, but for all Americans.

“Attorney Gray’s legacy of leadership was being the attorney for the people,” said Tafeni English, director of the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Civil Rights Memorial Center (CRMC), who first met Gray 30 years ago while in high school.

“He was never caught up in titles. He grew up in the segregated South. He could have been a preacher, but he wanted to fight Jim Crow laws and end segregation. This recognition is long overdue. We at the CRMC and those he fought for are extremely happy that he is receiving this honor.”

Gray was not the only civil rights leader who was honored today. Diane Nash, who led sit-ins, coordinated freedom rides and was jailed while pregnant for teaching nonviolent protest tactics to children in Tennessee, was also among the 17 people who were honored today with a Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Winning landmark rulings

Gray’s legal work led to a host of landmark Supreme Court rulings and federal government orders starting with Browder v. Gayle in 1956, the case that arose from the Montgomery Bus Boycott and galvanized the civil rights movement.

He took on a gerrymandered Tuskegee, Alabama, voting district that disenfranchised Black residents, resulting in another major Supreme Court ruling in 1960, Gomillion v. Lightfoot, when the court concluded the district was drawn with the sole purpose of depriving Black people of political power. His successful challenge to Alabama’s segregated public schools, colleges and universities was the first test case of the 1954 Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education and resulted in widespread school desegregation in 1967 – although it would take additional legal challenges until all American schools became fully desegregated.

Another landmark Supreme Court decision fundamentally reshaped defamation law and freedom of the press. And after the Supreme Court ruled in 1973 in favor of Gray’s class action lawsuit on behalf of survivors of the Tuskegee Experiment, possibly the most egregious case of racial discrimination in the history of modern medical research, Congress enacted the 1974 National Research Act. The act set ethical standards for medical research on human subjects.

The SPLC was among more than 50 organizations and individuals that supported Gray’s nomination for the Presidential Medal of Freedom. SPLC President and CEO Margaret Huang wrote in her letter to Biden that the organization “recognizes the achievements of Fred Gray in our mission to dismantle white supremacy and advance human rights for all people – a mission Fred Gray devoted his life and career to advance.”

Behind the scenes, professors Derryn Moten, chair of the history and political science department at Alabama State University; and Jonathan Entin of Case Western University School of Law – Gray’s alma mater – worked tirelessly to promote the nomination over the past 20 months. Other notable supporters included the presidents of Alabama colleges and universities that Gray helped to desegregate, the Alabama congressional delegation, the Congressional Black Caucus and U.S. Rep. Terri Sewell, who grew up in Selma and shepherded the nomination through Congress and the White House.

Sewell described the “full-court press” she and others made to “push it through the finish line while he’s still alive and we have the opportunity to honor him.” She recounted personally lobbying Vice President Kamala Harris, Cabinet members and Biden himself during a plane trip to a Troy, Alabama, factory that builds weaponry for Ukrainian fighters.

“My district includes [parts of] Montgomery, Birmingham and Selma – America’s civil rights district,” Sewell said. “There is nothing more important to my district that those heroes, known and unknown, get their due and recognition in the annals of civil rights.”

Brilliant legal mind

Gray was just 25 when 15-year-old Claudette Colvin was arrested for refusing to give up her seat to a white woman on a crowded Montgomery bus. Nine months later, in December 1955, Rosa Parks’ refusal to do the same led to the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Colvin and five other women became the original plaintiffs in Gray’s successful lawsuit to end bus segregation based on the 14th Amendment’s due process and equal protection clauses.

Bernard Lafayette first met Gray in Selma days after Lafayette’s former college roommate, John Lewis, and other voting rights marchers were savagely beaten by state troopers and sheriff’s deputies as they attempted to cross Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge on their way to Montgomery on March 7, 1965, a date later known as Bloody Sunday.

That night, Gray was hired to represent the nonviolent activists. The following day, he filed a lawsuit that two weeks later enabled the activists – by then 8,000-strong – to safely cross the bridge on a four-day, 54-mile march to Montgomery that culminated with King’s “How Long, Not Long” speech, delivered at the steps of the Alabama Capitol. The marches led to passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

In a recent interview with the SPLC, Lafayette recalled the modest man and Church of Christ preacher, who never called attention to himself – and “never gave up.”

“To have Fred Gray in your corner you felt very secure because you had someone with a lot of experience and knowledge,” Lafayette said. “You can’t lose if you never give up.”

What set Gray apart from other civil rights lawyers – aside from his winning record – was how during case preparation he would provide clients “more of an explanation than an argument,” Lafayette said.

“He would help us understand existing policies and laws and what changes had to take place to gain the rights we deserve. We would talk about our goals and behavior. We felt we had the right to do that [secure equality] and we needed to have the legal basis. He taught us that we were federal citizens, not just citizens of the state.”

Gray’s approach to arguing a case was also different.

“It wasn’t just to take our side and put the other side down, but he explained the law and how a particular position would be beneficial to both sides. He would try to make people see that a person’s color doesn’t necessarily define their limitations or ultimate capacity. The irony is that when he’s arguing a case in court, he represents the example he’s talking about. So, it wasn’t about winning and losing but more reaching reconciliation.”

For Gray’s many “firsts” in addition to his landmark litigation – first Black president of the National Bar Association, first Black president of the Alabama Bar Association, one of the first two Black members elected to the Alabama Legislature since the Reconstruction era – he has been an inspiration to lawyers, Black and white.

Lisa Borden was in private practice in 2011 working on death penalty litigation out of Birmingham when she was asked to write a brief for a U.S. Supreme Court case that Gray, two other former presidents of the Alabama Bar Association and former Alabama appellate judges were filing on behalf of a person on death row.

Borden, who is now the senior policy counsel for international advocacy at the SPLC, said of her past experience working with Gray, “He was long since a legend in Alabama and civil rights law, but at 80, he was very meticulous about his involvement, the legal strategy and his input. How he felt things should be phrased. He was a terrific mentor and writer. He made me a better lawyer.”

University of Alabama School of Law Professor Bryan Fair, an SPLC board member since 2013, said he and Gray occasionally still discuss the 91-year-old attorney’s ongoing legal cases. In 2010, at a symposium centered around Gray’s landmark cases, Fair announced his nomination of Gray for the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Fair told the SPLC, “From his modest beginning in Montgomery, to being forced to leave for law school [due to segregation], to going back to Alabama, saying ‘I’m going to use the legal system to destroy segregation,’ and still in his 20s using constitutional law to attack a system that he thought was fundamentally unfair to Black people, he is absolutely an inspiration. … I’m personally thrilled to see this recognition for such an important figure in the history of the United States.”

President Joe Biden awards the nation's highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, to civil rights attorney Fred Gray during a ceremony Thursday, July 7, 2022, in the East Room of the White House in Washington. (Credit: Susan Walsh/AP)